The documents presented below are linked to the articles accessible here.

French law faculties were set up by Napoleon to teach codified law. It was not until the Third Republic, however, that they truly began to modernize, with the specialization of teaching and the development of new disciplines. Until the Great War, while the Parisian faculty continued to dominate in terms of the number of students and staff, provincial faculties became more prominent on the academic scene.

The texts

Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.Digitalized document available here in French.

Under the Empire, in 1804, a dozen cities were allowed to reopen their faculty, under new conditions.

Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The law of 1896 was the major law organizing the universities under the Third Republic. In 1914, when France entered the war, universities were governed by this law, which is still in force today.

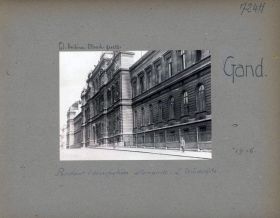

Source Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent/Bibliothèque de l’Université de Gand, BIB.197L007

Document numérisé consultable ici.

The 1835 law still governs the Belgian organization of higher education at the beginning of the war.

![<em>Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France</em>

<br><br>

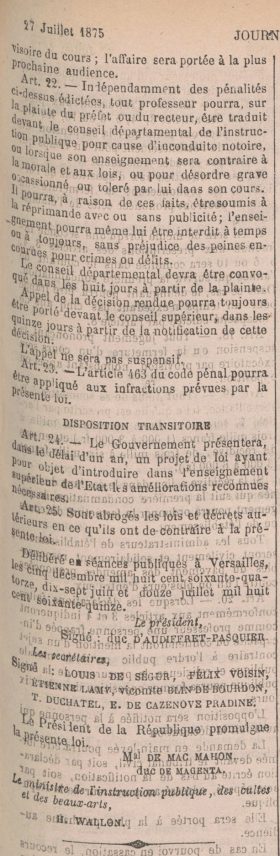

<strong>In a National Assembly polarized between Republicans on one side and clerical-Legitimists on the other, higher education became an ideological battleground. It was in this context that the freedom of higher education was proclaimed by the law of July 12, 1875, continuing the work of the Guizot Law of 1833 and the Falloux Law of 1850, which had enshrined the same freedom for primary and secondary education, respectively.

In concrete terms, the 1875 law put an end to the State’s monopoly over higher education by stipulating that “Any French citizen aged twenty-five years, who has incurred none of the incapacities provided for in Article 8 of this law, [and] legally formed associations with the purpose of higher education, may freely establish courses and institutions of higher education” (Article 2 of the Law of July 12, 1875).

This provision, subject only to obtaining a receipt from the rector delivered “immediately” after the filing of a declaration specifying the purpose of the proposed course, provoked sharp criticism from the outset—particularly concerning the scope of this freedom—and fueled Republican fears of religious congregations taking control of higher education.

These concerns explain the revision of the law in 1880, following the Republicans’ successes in Parliament in 1876 and 1877.</strong>](/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/10/Loi_relative_a_la_liberte_de_lenseignement_superieur_Journal_officiel_no204_7e_annee_27071875-scaled/1227146065.jpg)

In a National Assembly polarized between Republicans on one side and clerical-Legitimists on the other, higher education became an ideological battleground. It was in this context that the freedom of higher education was proclaimed by the law of July 12, 1875, continuing the work of the Guizot Law of 1833 and the Falloux Law of 1850, which had enshrined the same freedom for primary and secondary education, respectively. In concrete terms, the 1875 law put an end to the State’s monopoly over higher education by stipulating that “Any French citizen aged twenty-five years, who has incurred none of the incapacities provided for in Article 8 of this law, [and] legally formed associations with the purpose of higher education, may freely establish courses and institutions of higher education” (Article 2 of the Law of July 12, 1875). This provision, subject only to obtaining a receipt from the rector delivered “immediately” after the filing of a declaration specifying the purpose of the proposed course, provoked sharp criticism from the outset—particularly concerning the scope of this freedom—and fueled Republican fears of religious congregations taking control of higher education. These concerns explain the revision of the law in 1880, following the Republicans’ successes in Parliament in 1876 and 1877.

The law of March 18, 1880, on higher education takes the opposite stance to the law of the same name adopted five years earlier. This law, sponsored by the Republican Jules Ferry, then Minister of Public Instruction, aims to strengthen the role of the state in higher education, a role that had been significantly reduced since the law of 1875. Without revisiting the issue of freedom of education, the 1880 law gave state faculties and universities a monopoly on awarding degrees (Article 1 of the law) and reserved the titles “baccalaureate,” “license,” and “doctorate” for degrees awarded by these same faculties (Article 4). Furthermore, the now “free institutions of higher education” were deprived of the right to use the title of university. While these measures certainly strengthened the state's power over higher education, their main aim was to secularize it.

The institutions

Source: Cujas Library.

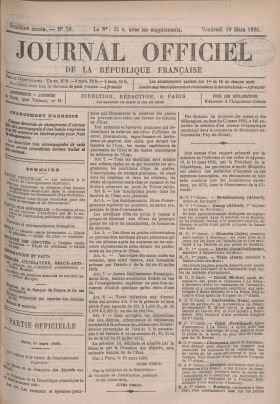

View of the Paris Faculty of Law around 1900. The building was designed in 1772 by the architect Soufflot. Its extension on rue Saint-Jacques was realized by Louis-Ernest Lheureux in the 1890s.

Source Bibliothèque Cujas, cote ARCHIVES 292-17.

Main room of the Paris Faculty of Law library between 1878 and 1898, built by architect Ernest Lheureux.

Source Bibliothèque Cujas.

Facade of the Paris Faculty of Law, rue saint-Jacques, inaugurated at the end of the 1890s.

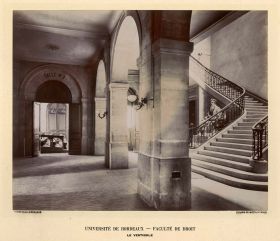

Source: Digitalized heritage collections of Bordeaux Montaigne, Histoire de l'université à Bordeaux, i.d. PL 8170-1_1871.Digitalized documentavailable here

As this document reports, a first speech by a dean of the faculty of law, for the solemn re-opening of the university, did not take place until 1871.

Source: Bordeaux Library.

![<p style=padding: 1.5em><em>Source: Archives of the Université Libre de Bruxelles</em><br/></br>

<strong>The Université Libre de Bruxelles was established between 1842 and 1928 in the Palais Granvelle, the former palace of Cardinal de Granvelle, who was an advisor to Philip II and the Governors General of the Netherlands. Built in the center of Brussels, near the Mont des Arts, between Rue des Sols and Rue de l'Impératrice, the Palais Granvelle had previously housed the Brabant Court d'Assises [Criminal Court]. After the war, the university authorities were forced to consider a new location because of the urban planning projects that affected Brussels. New buildings were constructed on the Solbosch plain from 1921 onwards. The installation of the University on the Solbosch - its current site - owes much to American aid, through the CRB Educational Foundation. The inauguration took place in 1928.</strong>](/wp-content/uploads/cache/2018/10/Palais-Granvelle/3522649121.jpg)

Source: Archives of the Université Libre de Bruxelles

The Université Libre de Bruxelles was established between 1842 and 1928 in the Palais Granvelle, the former palace of Cardinal de Granvelle, who was an advisor to Philip II and the Governors General of the Netherlands. Built in the center of Brussels, near the Mont des Arts, between Rue des Sols and Rue de l'Impératrice, the Palais Granvelle had previously housed the Brabant Court d'Assises [Criminal Court]. After the war, the university authorities were forced to consider a new location because of the urban planning projects that affected Brussels. New buildings were constructed on the Solbosch plain from 1921 onwards. The installation of the University on the Solbosch - its current site - owes much to American aid, through the CRB Educational Foundation. The inauguration took place in 1928.

![<em> Université Nouvelle - Rue de la Concorde </em>

<p style=padding: 1.5em><em>Source: Archives of the Université Libre de Bruxelles</em></br></p>

<p><strong>The New University is the result of a dissidence from the Université Libre de Bruxelles in 1894. It organized doctorates in several disciplines, including law. Imbued with socialist thought, it was run by Guillaume De Greef, a lawyer and one of the founding figures of Belgian sociology, who had given up his teaching position at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. The Université Nouvelle rented a building on rue de la Concorde, a street perpendicular to avenue Louise, not far from the Palais de Justice [Court House]. Before the war, it mainly welcomed foreign students.</strong></p>](/wp-content/uploads/cache/2018/10/Universite_nouvelle_Bruxelles-rue-de-la-concorde_R/2455225327.jpg)

Source: Archives of the Université Libre de Bruxelles

The New University is the result of a dissidence from the Université Libre de Bruxelles in 1894. It organized doctorates in several disciplines, including law. Imbued with socialist thought, it was run by Guillaume De Greef, a lawyer and one of the founding figures of Belgian sociology, who had given up his teaching position at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. The Université Nouvelle rented a building on rue de la Concorde, a street perpendicular to avenue Louise, not far from the Palais de Justice [Court House]. Before the war, it mainly welcomed foreign students.

Source: Valois album fund, VAL 482/031, coll. La contemporaine

Within the framework of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, the restructuring of higher education that took place with the law of September 25, 1816 led to the establishment of the State University of Ghent in 1817.

Source Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent/Bibliothèque de l’Université de Gand

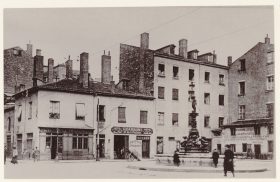

The Catholic Faculty of Law in Lyon opened its doors in November 1875 at 4bis Place Saint-Michel, now Place Antoine Vollon, on the site of the P. Bourdin bistro and coal yard, and the building behind it. It comprised a staff room, a lecture hall, a study room, an office, two lecture theaters, and a small library.

Cramped in its buildings on Place Vollon, the Catholic Faculty of Law in Lyon moved in November 1918 to the Hôtel de Cuzieu, at 30 Rue Sainte-Hélène.

The functioning

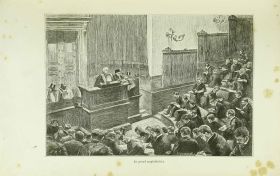

Source: Cujas Library, class. no 11.259

Source: Cujas Library, class. no ARCHIVES 292-5.

In France, the Faculty Board was made up of tenured professors and assistants. It met under the authority of the dean, and managed the accounts and the budget, gave its opinion on vacations and transfers of professorships, set the rules and regulations, organized conferences and competitions of the Faculty, and took care of matters regarding the teachings. In this photograph, the meeting of the Board of the Paris Faculty of Law was under the chairmanship of Dean Charles Lyon-Caen, which sets it between 1906 to 1911.

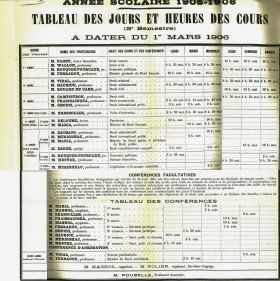

Source: Archives of Toulouse 1-Capitole University, Heritage registers, 2Z2-14 (1908-1924), p. 351.

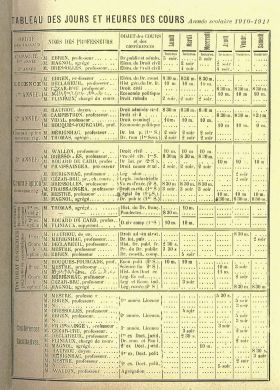

Source: Archives of Toulouse 1-Capitole University, Heritage registers, 2Z2-16 (1908-1924), p. 76.

![<p style=padding: 1.5em<em>Source: Archives of Toulouse 1-Capitole University, Heritage registers, 2Z2-16 (1908-1924), p. 124-127.</em></br></p>

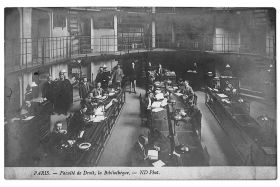

<strong>

The board of the Toulouse Faculty of Law deliberated during the meeting of April 25, 1912 on the passage from a system of notation by balls to a system of notation in figures. The choice made was to maintain the colored ball grading system. This practice was called into question by the decree of February 26, 1913, which modified the grading system in the university's bachelor's and doctoral examinations by adopting the system of numeral grading.</strong> <br>

<br><p style="font-size: 0.95em;">

Translation: "Session of April 25, 1912<br>In the year 1912 and on Thursday, April 25, at 2:00 p.m., the Faculty Board met in the regular meeting room at the invitation and under the chairmanship of Dean Hauriou.<br>

Present: M. Hauriou, M. Campistron, M. Bressolles, M. Rouard de Card, M. Mérignhac, M. Fraissaingea, M. Ebren, M. Declareuil, M. Thomas, M. Cézar-Bru, M. Magnol, M. Fliniaux, M. Perreau and M. Dugarçon<br>Excused : M. Houques-Fourcade<br>On leave: M. Wallon and M. Gheusi<br>On mission: M. Polin<br>The minutes of the previous meeting were read and adopted.<br>M. Thomas was elected secretary, replacing M. Fraissaingea, who asked to be relieved of his duties. The Dean thanked M. Fraissaingea for his good and long service to the faculty as secretary.<br>The Dean read out a dispatch dated April 22, in which the Minister informed that he had postponed the date of the elections for the renewal of the Superior Council of Public Instruction: the first round of voting will take place on May 17 (instead of May 14) and the second round, if necessary, on Friday, May 31.<br>Agenda:<br>

I. Optional Conference Fee Waivers<br>

Because the number of paying students allows for eight waivers, the faculty grants the waiver to the following 6 students who requested it:<br>M. Séris, 1<sup>st</sup> year student<br>M. Chansou, 2<sup>nd</sup> year student<br>M. Bennet, 3<sup>rd</sup> year student<br>M. Cassan, 3<sup>rd</sup> year student<br>M. Rioufoh, 3<sup>rd</sup> year student<br>M. Duplan, political science PhD student<br>II. Opinion to be given on the proposed substitution of the number grading system for the ball grading system <br>The Dean read the following ministerial dispatch dated March 26:<br>'A certain number of law schools have expressed the wish that, for the bachelor's and doctoral examinations, the system of notation in balls be substituted for the system of notation in numbers from 0 to 20.<br>I would be grateful if you would submit this wish to the Toulouse Faculty of Law and invite them to deliberate on it.<br>Please send me its deliberation, along with your personal opinion.' […] "</p>](/wp-content/uploads/cache/2018/10/Délibération-de-lassemblée-de-la-faculté-de-Toulouse-sur-la-notation-par-boules-de-couleur-des-étudiants-25-avril-1912_1/2451443915.jpg)

Translation: "Session of April 25, 1912

In the year 1912 and on Thursday, April 25, at 2:00 p.m., the Faculty Board met in the regular meeting room at the invitation and under the chairmanship of Dean Hauriou.

Present: M. Hauriou, M. Campistron, M. Bressolles, M. Rouard de Card, M. Mérignhac, M. Fraissaingea, M. Ebren, M. Declareuil, M. Thomas, M. Cézar-Bru, M. Magnol, M. Fliniaux, M. Perreau and M. Dugarçon

Excused : M. Houques-Fourcade

On leave: M. Wallon and M. Gheusi

On mission: M. Polin

The minutes of the previous meeting were read and adopted.

M. Thomas was elected secretary, replacing M. Fraissaingea, who asked to be relieved of his duties. The Dean thanked M. Fraissaingea for his good and long service to the faculty as secretary.

The Dean read out a dispatch dated April 22, in which the Minister informed that he had postponed the date of the elections for the renewal of the Superior Council of Public Instruction: the first round of voting will take place on May 17 (instead of May 14) and the second round, if necessary, on Friday, May 31.

Agenda:

I. Optional Conference Fee Waivers

Because the number of paying students allows for eight waivers, the faculty grants the waiver to the following 6 students who requested it:

M. Séris, 1st year student

M. Chansou, 2nd year student

M. Bennet, 3rd year student

M. Cassan, 3rd year student

M. Rioufoh, 3rd year student

M. Duplan, political science PhD student

II. Opinion to be given on the proposed substitution of the number grading system for the ball grading system

The Dean read the following ministerial dispatch dated March 26:

'A certain number of law schools have expressed the wish that, for the bachelor's and doctoral examinations, the system of notation in balls be substituted for the system of notation in numbers from 0 to 20.

I would be grateful if you would submit this wish to the Toulouse Faculty of Law and invite them to deliberate on it.

Please send me its deliberation, along with your personal opinion.' […] "

![<p style=padding: 1.5em<em>Source: Archives of Toulouse 1-Capitole University, Heritage registers, 2Z2-16 (1908-1924), p. 124-127.</em></br></p>

Translation: "[…] The Dean read to his colleagues the following draft resolution:<br>The Toulouse Faculty of Law is of the opinion to maintain the grading of the exams by the ball system for the following reasons:<br>1°) They observe that one of the criticisms leveled at this system is that it is "archaic" and it does not seem to them that the fact that an institution is old constitutes a decisive reason to demand its abolition or transformation: there are, in law schools, other archaic institutions or contents, for example, the habit that has been preserved of holding courses and examinations in black or red robes; should this habit also be abolished?<br>2°) Considering the grading by the ball system, the Faculty notes that it is appropriate to distinguish in any system of grades given by a jury, the question of the grading itself and that of the totalization of the grades.<br>- As far as the totaling of scores is concerned, it must be conceded that the system of numbers is simpler than that of balls: numbers add up naturally, whereas balls do not add up. But this disadvantage of the balls not adding up has been remedied by legal combinations of balls which leave no uncertainty as to the result of the examination. That if these combinations seem to have been badly established and if it is felt that a candidate should not be declared eligible with two reds and one red-black, nothing is easier than to modify the combination by a new regulation. It is also important to note that, in essence, totalization is not so much a simple arithmetic operation as a means of determining the sufficiency of the examination: sufficiency as a whole, which is reflected in a minimum total of points; sufficiency in each subject, which is reflected in a minimum mark for each question. Now, this observation can be made with balls as well as with numbers, and we do not see that in this respect the notation by numbers is a necessity<br>- As far as notation is concerned, it seems that the ball system is superior to the number system. To establish this, it is necessary to recall a number of facts.<br>First of all, the basis of all grading is the grades that can be listed as follows: very poor, poor, fair, fairly good, good: all the other grading methods are simply equivalents of the grades: white means "good", just as grades 18 to 20 in the zero to twenty scale also mean "good".<br>Secondly, it is good to know that in practice, the ball system works with nuances that come from the fact that each ball can be considered as good or bad, as strong or weak, or as pure and simple. One gives a good white or a weak white or a pure and simple white, a good red-white or a bad red-white or a pure and simple red-white, and each of the five balls being thus multiplied by three nuances, one arrives at a total of fifteen notes at the disposal of the examiner and it is, in short, as if he had a scale of numbers from 1 to 15, as it results from the following table: […]"

<table border="1" width="100%">

<tr>

<td width="15%" align="middle" style="vertical-align:middle">black</td>

<td width="57%" style="font-size:0.80em;">bad<br />pure and simple<br />diminished</td>

<td width="15%" align="middle" style="vertical-align:middle">very bad</td>

<td width="3%" style="font-size:0.80em;" align="middle">1<br>2<br>3</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="middle" style="vertical-align:middle">red black</td>

<td style="font-size:0.75em;">mauvaise<br>pure and simple<br>good</td>

<td align="middle" style="vertical-align:middle">bad</td>

<td style="font-size:0.80em;" align="middle">4<br>5<br>6</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="middle" style="vertical-align:middle">red</td>

<td style="font-size:0.75em;">bad<br>pure and simple<br>good</td>

<td align="middle" style="vertical-align:middle">passable</td>

<td style="font-size:0.80em;" align="middle">7<br>8<br>9</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="middle" style="vertical-align:middle">white red</td>

<td style="font-size:0.75em;">bad<br>pure and simple<br>good</td>

<td align="middle" style="vertical-align:middle">good enough</td>

<td style="font-size:0.80em;" align="middle">10<br>11<br>12</td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>](/wp-content/uploads/cache/2018/10/Délibération-de-lassemblée-de-la-faculté-de-Toulouse-sur-la-notation-par-boules-de-couleur-des-étudiants-25-avril-1912_2/3208383434.jpg)

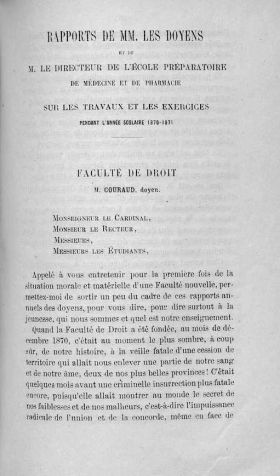

The Toulouse Faculty of Law is of the opinion to maintain the grading of the exams by the ball system for the following reasons:

1°) They observe that one of the criticisms leveled at this system is that it is "archaic" and it does not seem to them that the fact that an institution is old constitutes a decisive reason to demand its abolition or transformation: there are, in law schools, other archaic institutions or contents, for example, the habit that has been preserved of holding courses and examinations in black or red robes; should this habit also be abolished?

2°) Considering the grading by the ball system, the Faculty notes that it is appropriate to distinguish in any system of grades given by a jury, the question of the grading itself and that of the totalization of the grades.

- As far as the totaling of scores is concerned, it must be conceded that the system of numbers is simpler than that of balls: numbers add up naturally, whereas balls do not add up. But this disadvantage of the balls not adding up has been remedied by legal combinations of balls which leave no uncertainty as to the result of the examination. That if these combinations seem to have been badly established and if it is felt that a candidate should not be declared eligible with two reds and one red-black, nothing is easier than to modify the combination by a new regulation. It is also important to note that, in essence, totalization is not so much a simple arithmetic operation as a means of determining the sufficiency of the examination: sufficiency as a whole, which is reflected in a minimum total of points; sufficiency in each subject, which is reflected in a minimum mark for each question. Now, this observation can be made with balls as well as with numbers, and we do not see that in this respect the notation by numbers is a necessity

- As far as notation is concerned, it seems that the ball system is superior to the number system. To establish this, it is necessary to recall a number of facts.

First of all, the basis of all grading is the grades that can be listed as follows: very poor, poor, fair, fairly good, good: all the other grading methods are simply equivalents of the grades: white means "good", just as grades 18 to 20 in the zero to twenty scale also mean "good".

Secondly, it is good to know that in practice, the ball system works with nuances that come from the fact that each ball can be considered as good or bad, as strong or weak, or as pure and simple. One gives a good white or a weak white or a pure and simple white, a good red-white or a bad red-white or a pure and simple red-white, and each of the five balls being thus multiplied by three nuances, one arrives at a total of fifteen notes at the disposal of the examiner and it is, in short, as if he had a scale of numbers from 1 to 15, as it results from the following table: […]"

| black | bad pure and simple diminished |

very bad | 1 2 3 |

| red black | mauvaise pure and simple good |

bad | 4 5 6 |

| red | bad pure and simple good |

passable | 7 8 9 |

| white red | bad pure and simple good |

good enough | 10 11 12 |

![<p style=padding: 1.5em<em>Source: Archives of Toulouse 1-Capitole University, Heritage registers, 2Z2-16 (1908-1924), p. 124-127.</em></br></p>

Translation : "[…] It is true that in the totalization, the nuances of each ball disappear in that they do not appear in the result: there appear only pure and simple balls, but everyone knows that these pure and simple balls of the result are obtained in the deliberation of the jury by the compensation of the nuances; a good white red and a bad red make two reds; thus, the nuances have nevertheless their effectiveness.<br>Now, and this is the point on which it is advisable to insist, in the scale of numbers, there are also nuances, but they do not constitute, as in the system of the balls, a group organized around the pure and simple note and they do not play with the same safety.<br>Let's take, in the previous table, the shades corresponding to the mention "passable", either in the ball system or in the number system and compare them.<br>In the system of balls, the pure and simple passable is symbolized by the red ball, but, by comparison with the pure and simple red, two nuances are established which are the good red and the bad red; these two nuances are easy to establish either by their comparison with the pure and simple, or by their opposition between them; In the system of numbers, from zero to 15, a group of three numbers corresponds to the mention "fair", these are numbers 7, 8, 9, but this group is not organized, there is no center. There is no indication that 8 corresponds to the pure and simple mention "passable" and that 7 and 9 are only strong or weak nuances of it. The result is a greater degree of uncertainty in the marking, because there is nothing to say that an examiner will not take as a correspondence to passable 7, another 8, another 9, etc..<br>Our table of concordance of the shaded balls with the numbers from 1 to 15 reduces to a question of words the question of the substitution of numbers for balls, which shows how sterile the proposed change is at bottom, how idle the discussion is. And by realizing this, we return in favor of tradition an argument which one pretends to direct against it. Our system is archaic: but, because of this very fact, we are used to it, we know it, it is an instrument that we handle with ease and safety, which it is therefore advantageous to keep rather than to have recourse to a new instrument, it being proven that this new instrument does not present a certain superiority over the one that we have shaped and perfected in practice.

Following this reading and after an exchange of comments, the faculty voted 13-2 to retain ball grading..<br>III. Opinion to be given on the addition of a written test to the three Bachelor's degree exams<br>The Dean read the following ministerial dispatch dated March 28, 1912:<br>'I was delivered the following wish:<br>

That written compositions be organized in the three law degree examinations, it being understood that the written test will be strictly eliminatory and that the candidate will not be allowed to take either part of the oral examination. […]"](/wp-content/uploads/cache/2018/10/Délibération-de-lassemblée-de-la-faculté-de-Toulouse-sur-la-notation-par-boules-de-couleur-des-étudiants-25-avril-1912_3/3684254411.jpg)

Now, and this is the point on which it is advisable to insist, in the scale of numbers, there are also nuances, but they do not constitute, as in the system of the balls, a group organized around the pure and simple note and they do not play with the same safety.

Let's take, in the previous table, the shades corresponding to the mention "passable", either in the ball system or in the number system and compare them.

In the system of balls, the pure and simple passable is symbolized by the red ball, but, by comparison with the pure and simple red, two nuances are established which are the good red and the bad red; these two nuances are easy to establish either by their comparison with the pure and simple, or by their opposition between them; In the system of numbers, from zero to 15, a group of three numbers corresponds to the mention "fair", these are numbers 7, 8, 9, but this group is not organized, there is no center. There is no indication that 8 corresponds to the pure and simple mention "passable" and that 7 and 9 are only strong or weak nuances of it. The result is a greater degree of uncertainty in the marking, because there is nothing to say that an examiner will not take as a correspondence to passable 7, another 8, another 9, etc..

Our table of concordance of the shaded balls with the numbers from 1 to 15 reduces to a question of words the question of the substitution of numbers for balls, which shows how sterile the proposed change is at bottom, how idle the discussion is. And by realizing this, we return in favor of tradition an argument which one pretends to direct against it. Our system is archaic: but, because of this very fact, we are used to it, we know it, it is an instrument that we handle with ease and safety, which it is therefore advantageous to keep rather than to have recourse to a new instrument, it being proven that this new instrument does not present a certain superiority over the one that we have shaped and perfected in practice. Following this reading and after an exchange of comments, the faculty voted 13-2 to retain ball grading..

III. Opinion to be given on the addition of a written test to the three Bachelor's degree exams

The Dean read the following ministerial dispatch dated March 28, 1912:

'I was delivered the following wish:

That written compositions be organized in the three law degree examinations, it being understood that the written test will be strictly eliminatory and that the candidate will not be allowed to take either part of the oral examination. […]"

![<p style=padding: 1.5em<em>Source: Archives of Toulouse 1-Capitole University, Heritage registers, 2Z2-16 (1908-1924), p. 124-127.</em></br></p>

Translation: "[…] 'In support of this wish, the following considerations are invoked:<br>1°) The law examinations are the only examinations for which there are no written eligibility tests for the oral examination;<br>2°) The written test provides the best way to accurately assess the value of the candidates.<br>I would be grateful if you would submit this wish to the Assembly of the Toulouse Faculty of Law and invite it to deliberate on it.<br>Please send me their deliberations, along with your personal opinion.'<br>

An exchange of views took place following this reading and the result of the deliberation was as follows:<br>The Toulouse faculty adopts in principle the introduction of written compositions in the Bachelor's degree examinations (9 to 6) under the following conditions:<br>1° There will be, in each year, two written compositions: one, on civil law, the other, on another subject of the year chosen by lot (aye: 8 votes, nay: 3)

2° Each Faculty will be in charge of correcting the compositions of its students and will make an internal regulation for this purpose; in no case, there can be no question of correcting by an inter-university organization (unanimity)<br>Total vote: 8 against 7.<br>There being no further business, the meeting was adjourned at four o'clock.<br>The Secretary of the Assembly [signature of P. Thomas]. <br>The Dean-President[signature of M. Hauriou]"</p>](/wp-content/uploads/cache/2018/10/Délibération-de-lassemblée-de-la-faculté-de-Toulouse-sur-la-notation-par-boules-de-couleur-des-étudiants-25-avril-1912_4/1499913454.jpg)

1°) The law examinations are the only examinations for which there are no written eligibility tests for the oral examination;

2°) The written test provides the best way to accurately assess the value of the candidates.

I would be grateful if you would submit this wish to the Assembly of the Toulouse Faculty of Law and invite it to deliberate on it.

Please send me their deliberations, along with your personal opinion.'

An exchange of views took place following this reading and the result of the deliberation was as follows:

The Toulouse faculty adopts in principle the introduction of written compositions in the Bachelor's degree examinations (9 to 6) under the following conditions:

1° There will be, in each year, two written compositions: one, on civil law, the other, on another subject of the year chosen by lot (aye: 8 votes, nay: 3) 2° Each Faculty will be in charge of correcting the compositions of its students and will make an internal regulation for this purpose; in no case, there can be no question of correcting by an inter-university organization (unanimity)

Total vote: 8 against 7.

There being no further business, the meeting was adjourned at four o'clock.

The Secretary of the Assembly [signature of P. Thomas].

The Dean-President[signature of M. Hauriou]"