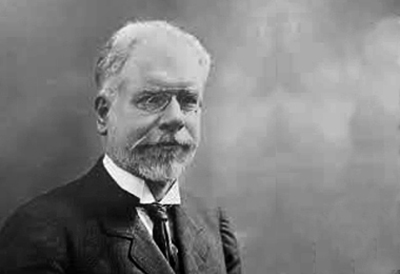

Pierre Marie Nicolas Léon Duguit was born on February 4, 1859 in Libourne, Gironde. Brilliant studies, both in high school and university, allowed him to obtain the title of doctor at twenty-two years old. Thanks to an age exemption, he was granted tenure the following year. He taught the legal history in Caen, before returning to Bordeaux in November 1886. There, he met sociologist Émile Durkheim, who strongly influenced his legal thinking, tinging it with legal sociology.

In parallel with his teaching, Duguit became involved in politics. He claimed to belong to the Léon Bourgeois’s “solidierist” current, represented in Bordeaux by Durkheim. According to Duguit, a jurist has a social role, that of “guide” towards the legislator, because of his discoveries of social laws. In this perspective, he intervened in the Society of Legislative Studies, created in 1902 and that he became involved as a professional in politics. He was elected in 1908 to the Bordeaux city council on a list of the Democratic Republican Union, but was however outvoted in the legislative elections of 1914, in Libourne, which put a brake on his political ambitions.

August 1, 1914 : General mobilization was decreed in France, announcing the country’s entry into war. In Bordeaux, the announcement of this event, placarded on the Saint Jean train station, disrupted university activities, especially on an economic level. The number of students and staff in Bordeaux faculties was seriously affected by conscription.

However, the Bordeaux Faculty of Law participated even more than its counterparts in the war effort. Due to the meteoric German breakthrough in the north of the country, the front fixing itself thirty kilometers away from Paris before being repulsed during the Battle of the Marne, the French government temporarily settled in Bordeaux, in September 1914. The Faculty of Law then housed all the staff of the Ministry of Public Instruction. Nevertheless, the number of staff had been reduced, as only the bulk of its services were actually relocated. The faculty board room became the minister’s office and Léon Duguit, then the dean’s assessor since 1901, a position held by Henri Monnier, met with the minister’s chief of staff. As for the director of secondary education, historian Alfred Coville, whom Duguit had met in Caen, he settled in one of the large rooms of the faculty.

For Léon Duguit, the mobilization manifested mainly in the form of a commitment of administrator, in a military hospital. This is how he took charge, throughout the conflict, of the military hospital on rue Ségalier. Having been appointed a member of the civil hospices commission of Bordeaux a few years earlier, while he was still a member of the city council, he chose to continue this activity throughout the conflict, in parallel with his still effective participation in the higher board of public assistance.

The Great War was also the scene of great human tragedies, between the massacres of the front and the trauma of the civilian populations located at the back. Thus, many jurists engaged in a merciless struggle against the German Kultur, both militarily and intellectually, lost friends and relatives during the conflict. Léon Duguit, married in 1892 and father of two sons, Pierre and Michel, lost one of them, the eldest, in Verdun. C. Chazalet, in a speech given in 1929 in honor of Léon Duguit, reflected on this tragic event : “M. Léon Duguit portait au cœur une blessure profonde : l’un de ses fils, pendant la Grande Guerre, était tombé en soldat sous les plis du drapeau tricolore pour que la France vive […]. L’enfant est resté dans un des cimetières de Verdun où M. et Mme Duguit allaient, il y a à peine un mois, porter en pleurant des fleurs sur sa tombe [Mr. Léon Duguit bore a deep wound in his heart: one of his sons, during the Great War, had fallen as a soldier under the folds of the tricolor flag so that France might live on […]. The child remained in one of the cemeteries of Verdun where M. and Mme. Duguit went, barely a month ago, to carry flowers and weep on his grave].”

For some, it was this loss that directed his thinking towards a new concept : that of the feeling of justice. This feeling would have become the basis of objective law, which was later strongly criticized. Critics saw it as a “droit naturel qui s’ignore [natural law that does not know it]”, or that would not name itself. For others and according to more recent work, this jusnaturalist turn would not date from this tragic event, namely the loss of his son in battle, because his positions on “legal conscience” and on this fundamental search for “justice” long preceded the conflict.

In the aftermath of the Great War, Léon Duguit wrote two tributes to fellow Bordeaux jurists, including the honorary dean of the faculty, professor and knight of the Légion d’honneur Henri Monnier. The latter, a great patriot who participated in the War of 1870, but too old for that of 1914, lost one of his sons on the eve of the Armistice, swept away by the Spanish flu epidemic that hit Europe so hard. Duguit, in his speech delivered on May 16, 1920 at the funeral, recalled the great moments of this professor whom he met in Caen and who, despite the loss of a child and his advanced age, continued to give lectures until the time when ” la maladie fut plus forte que la volonté. [Il tomba] frappé comme un soldat blessé au champ de bataille. C’était pour ne plus se relever [the disease was stronger than the will. [He fell] struck like a wounded soldier on the battlefield. It would be never to stand up again].” The second tribute, published in the Revue philomathique in October-December 1920, was written in honor of Gustave Chéneaux, who died at the front on April 29, 1915, on the battlefield of Les Éparges, at the age of forty-six. “Ainsi disparaissait dans la tourmente une belle intelligence, un noble cœur, un grand caractère [Thus disappeared in turmoil a beautiful intelligence, a noble heart, a great character],” Duguit lamented.

At the outbreak of the Great War, French scholars “went to the frontline” and vigorously opposed the German scientific model. Léon Duguit associated himself with this doctrinal assault, although he wrote little during the war. His main contribution to the “legal frontline” was a critique of the thinking of Kant and Hegel of November 1917, in an article initially proposed to the American public : “en vérité, je ris quand je vois quelques-uns de mes jeunes collègues […] venant dire : l’Allemagne moderne, absolutiste et impérialiste, ce n’est plus l’Allemagne de Kant, le philosophe qui a fondé sur des bases indestructibles l’autonomie de la personne humaine, le droit imprescriptible de l’individu contre la puissance de l’État ; c’est l’Allemagne de Hegel et de Ihering. Non, qu’on n’oppose pas Kant et Hegel. L’un et l’autre ont préparé la même œuvre ; comme Hegel, Kant, malgré son impératif catégorique, malgré son rêve de paix perpétuelle, a été un des grands artisans des conceptions impérialistes et absolutistes de l’Allemagne actuelle [In truth, I laugh when I see some of my young colleagues […] coming to say : modern, absolutist and imperialist Germany, it is no longer the Germany of Kant, the philosopher who founded on indestructible foundations the autonomy of the human person, the imprescriptible right of the individual against the power of the State ; it is the Germany of Hegel and Ihering. No, don’t let Kant and Hegel be pitted against each other. Both prepared the same work ; like Hegel, Kant, despite his categorical imperative, despite his dream of perpetual peace, was one of the great architects of the imperialist and absolutist conceptions of present-day Germany]” (“Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Kant et Hegel”, Revue de droit public, 1918). For Duguit, Kant and Hegel went even further than Rousseau, since they “deified” the State and its power, thus helping to make it a dangerous weapon against the law.

This opposition to German science did not, however, date back to 1914 and the outbreak of the conflict. Indeed, already at the beginning of the century, Duguit reproached the founder of the Historical School of Law, Prussian jurist Friedrich Carl von Savigny, his theory of fiction. In this criticism, he was already attacking the foundations of German science of the State, which he attributed to Jhering and which was itself inspired by Jellinek and his book Systemder öffentlichen subjektiven Rechte (1892). Duguit thus had developed his own theory according to which the power of the State should no longer be based on “imperium“, that is to say, its power and sovereignty, but on its mission, that of being at the service of the community. He concluded that Jhering, like Jellinek, “légitiment ainsi tous les actes tyranniques à l’intérieur, tous les brigandages à l’extérieur. Invasion et pillage de la Belgique, incendie de Louvain, massacre des enfants et des femmes, torpillage du Lusitania, tous les crimes abominables qui ont rempli le monde d’horreur étaient d’avance justifiés par les deux plus grands jurisconsultes de l’Allemagne moderne [thus legitimized all tyrannical acts inside, all robberies outside. Invasion and plunder of Belgium, burning of Leuven, massacre of children and women, torpedoing of the Lusitania, all the abominable crimes that have filled the world with horror were justified in advance by the two greatest jurists of modern Germany]” (La doctrine allemande de l’auto-limitation de l’État [The German Doctrine of the Self-Limitation of the State], 1919).

Similarly, during this period of world conflict, Duguit intervened in connection with a judgment rendered on the occasion of an incident in the city of Bordeaux. This judgment was at the origin of an intellectual confrontation between Duguit and the dean of Toulouse, Maurice Hauriou. It was one of the manifestations of the perpetual division that reigned among French constitutionalists, despite the “legal frontline”. This decision of the Council of State was published in the pages of Le Temps on April 1st, 1916. It focused on the financial situation of a gas company, whose economic survival has become very precarious since the outbreak of the war due to the explosion in the price of coal. At first, the company turned against the city of Bordeaux in order to obtain compensation for the additional cost it had to bear when it could not increase its prices. The prefecture rejected the claim, but it was disapproved by the Conseil d’Etat (highest administrative Court in France), which granted the company compensation. For Léon Duguit, the Conseil d’Etat encroached here on the prerogatives of legislation, which was contested by his Toulouse counterpart, who considered it a “duty” of the Conseil d’Etat to advance the law and be “progressive” regarding private law when it became necessary.

Also, from 1914 to 1945, the idea of a specifically “French” legal culture was developed and exported, conceived as an active support for the French political model, culture and diplomacy. In the 19th century, the emergence of this French model was laborious. But, from the beginning of the 20th century, the law became a determined ally in the affirmation of the identity of the Nation. He made it possible to oppose, alongside Ernest Renan (Qu’est-ce qu’une nation ? [What is a nation?], 1887), Johann Fichte or Johann Herder’s “German” vision. This “French spirit” was viscerally opposed to the German model and presented itself as the opponent of authoritarianism, which Duguit vigorously condemned in his doctrinal assaults on the German theory of the state. This French spirit presented itself as fiercely liberal and democratic, in favor of reason and the “scientific spirit”. These same commitments can be found in the reflection of the Bordeaux professor in Le pragmatisme juridique, published in 1924. Thus, symbol of the struggle against the former Germanic volksgeist, whose empire was defeated with the Great War, this French “genius” was illustrated by his clarity, rigor, science and morality.

In this context, Léon Duguit multiplied conferences abroad, exposed his own theories and thus participated in the influence of his university. Because of this intense intellectual activity, the rector of the Bordeaux academy noted about him in 1915-1916 that he became “un maître [a master]”, “de notoriété plus qu’européenne [of more than European notoriety]”. From then on, he participated greatly in the export of this French legal culture, later becoming dean of the Bordeaux Faculty of Law from 1919 to 1928. He was also a member of the university board for 20 years (since 1901), of the Advisory Committee on Public Education and Secretary General of the Alliance française régionale. Drawing the portrait of the Bordeaux jurist, Quintiliano Saldana wrote in a Madrid newspaper that “le professeur Duguit était, en droit, l’homme représentatif du génie français. Il est parvenu à être l’une – du moins l’une des plus grandes – célébrités juridique de notre temps. […] Sa serviette noire au bras, la chevelure grise sous l’aile d’ébène de son chapeau mou, nous le voyons, entre les deux pointes de sa jaquette et de sa barbe, grand, souriant, traverser les continents et croiser les mers durant quinze ans : de 1911 à 1926 [Professor Duguit was, in law, the representative man of the French genius. He managed to be at least one of the greatest legal celebrities of our time. […] His black robe on his arm, gray hair under the ebony wing of his soft hat, we see him, between the two points of his jacket and his beard, tall, smiling, crossing continents and seas for fifteen years : from 1911 to 1926]”. He enjoyed a great reputation until his last moments, as much with his colleagues as with his students. He died on December 18, 1928, in Bordeaux, after having presided over an aggregation examination from which he emerged exhausted. Léon Duguit, through his writings and his engagements, greatly contributed to the international reputation of the Bordeaux law school.

Nicolas Llesta Ferran, PhD student (University of Bordeaux)

Bibliography

Audren Frédéric, Halpérin Jean-Louis, La culture juridique française. Entre mythes et réalités : xixe–xxe siècles, Paris, France, CNRS, 2013.

Duguit Léon, Les transformations générales du droit privé depuis le Code Napoléon, Paris, Librairie Félix Alcan, 1912.

—, Le pragmatisme juridique (1923), présentation et traduction de Simon Gilbert, Paris, éditions La mémoire du droit, 2008.

García Villegas Mauricio, Lejeune Aude, « La sociologie du droit en France : De deux sociologies à la création d’un projet pluridisciplinaire ? », Revue interdisciplinaire d’études juridiques, vol. 66, no 1, 2011.

Giacuzzo Jean-François, « Un regard sur les publicistes français montés au ‘front intellectuel’ de 1914 à 1918 », dans Jus politicum : revue de droit politique, no 12, 2014, http://juspoliticum.com/article/Un-regard-sur-les-publicistes-francais-montes-au-front-intellectuel-de-1914-1918-884.html (consulté le 25/07/2018).

Hakim Nader, Melleray Fabrice (dir.), Le renouveau de la doctrine française : les grands auteurs de la pensée juridique au tournant du xxe siècle, Paris, France, Dalloz, 2009.

Hakim Nader, « Duguit et les privatistes », dans Autour de Léon Duguit, Colloque commémoratif du 150e anniversaire de la naissance du doyen Léon Duguit à Bordeaux le 29-30 mai 2009, sous la direction de Fabrice Melleray, Bruylant, 2011.

Jaubert Pierre, Centenaire de la faculté de droit, Annales de la faculté de droit des sciences sociales et politiques et de la faculté des sciences économiques, édition Bière, Bordeaux, 1976.

Halpérin Jean-Louis, « Louis Renault », dans Patrick Arabeyre, Jean-Louis Halpérin, Jacques Krynen (dir.), Dictionnaire historique des juristes français : xiie–xxe siècle, Paris, France, Presses universitaires de France, 2007, p. 660.

Pacteau Bernard, « Léon Duguit à Bordeaux, un doyen dans sa ville », Thémis dans la cité : contribution à l’histoire contemporaine des facultés de droit et des juristes, sous la direction de Nader Hakim et Marc Malherbe, PUF, 2009.