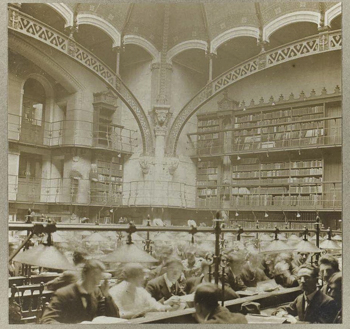

At the beginning of August 1914, when war broke out, the library of the Faculty of Law of Paris was a well-established and ever-expanding institution (by comparison, see the article on the library of Toulouse).

Its development had begun thirty-eight years earlier, starting in 1876, with the appointment of its first professional librarian, Paul Viollet. Reflecting a desire to move the structure out of its embryonic state, this appointment was accompanied by architectural construction, an increase in budget and an increase in the number of staff members.

Thus, between 1876 and 1914, under the leadership and direction of Viollet, the library grew from 20 to nearly 300 seats, from 15,000 to 112,000 books, from a few dozen to about 600 periodical subscriptions, from two to ten staff members, with reading rooms and conservation stores built in two stages, between 1876 and 1878 and between 1893 and 1897.

As the academic year 1913-1914 drew to a close, the library was still in this development logic, and had just experienced its most important year in terms of new book acquisitions.

August-November 1914 : the shock

In 1914, the library’s rules, unchanged since 1911, provided that the library remained open to the public until the end of the examinations in early August.

The summer closure was usually used for major cleaning, storage, and processings left on hold. The outbreak of hostilities swept this routine away.

As a direct consequence, the number of staff was halved : out of the ten staff members in the library, five were mobilized as early as August 1914. Library aide Maguer would never return, killed in combat in October 1914.

As in the entire administration, according to a memorandum of September 1st, all non-mobilized personnel are located, and either retained or recalled to their posts. In the Faculty of Law, only administrative staff and library staff were concerned (since courses did not resume until November, professors were exempted). For the library, Dean Larnaude and Paul Viollet took charge on August 31st of bringing the four remaining agents back.

Other decisions were taken immediately : while the Rector requested in early September that all the precious collections (archives, manuscripts, rare and precious books) be sheltered, Viollet had been faster than him, and they were already inventoried, removed from their usual places of storage, and placed in crates in the cellars of the faculty, by late August.

Moreover, the administration had to put itself at the service of the war effort and finances were redirected : as early as September the rector asked the deans to suspend all material expenditures which were not absolutely essential, and the university received instructions from the ministry in October requiring henceforth not only the freezing of all spending, but even the cancellation of all orders which could still be canceled. Paul Viollet contacted booksellers, bookbinders, heaters and other service providers to inform them of the consequences of the instructions received. Some were reluctant, arguing that the orders were already being processed, and the library still received an order for books for the benefit of the Cairo School of Law in autumn, which would remain blocked in Paris throughout the war.

Regarding collections, the delivery of thesis to German universities stopped in September at the request of the Rector, and, to avoid losses, the latter also required the suspension of interlibrary loans starting in December, and more generally any transmission of books from one city to another.

Thus, between August and November 1914, half of the Paris Faculty of Law’s library staff, part of its collections, and almost all of its budget were cut off. In addition, starting at the beginning of the school year, evening sessions had to be cancelled, as the presence of light could attract danger in the event of an enemy attack. All these constraints continued throughout the war. And as if to make this difficult period even more difficult, Paul Viollet, guardian figure of the place, died on November 22, 1914, roughly after the beginning of the school year ; he was not replaced until February 1918.

December 1914-February 1918 : adaptation and status quo

Paul Viollet, Jules Rousselle, Jean Gautier, Lefeuvre, Antoine Pradel, Albert Hissler, Eugène Brière, Émile Gravel, Hervé Maguer, Panouillot ; this was the library team of the Paris Faculty of Law at the beginning of the war, with its chief librarian, its three librarians and its six aides.

Two librarians and three aides were mobilized in August 1914 : Jean Gautier, Lefeuvre, Panouillot, Émile Gravel and Hervé Maguer.

In December 1914, following the death of Paul Viollet, only four of them remained to hold the library, headed by Jules Rousselle. He was the one standing out during this period, very much against his will. He took over the management of the library upon Viollet’s death, and remained in charge until the beginning of 1918. Rousselle arrived at the library on May 23, 1878, after having been a farmer and employee at Le Bon Marché. He was Viollet’s first hire upon his arrival, at the time as a library aide. He was promoted to deputy librarian on January 1st, 1899, and to librarian on January 1st, 1912. He finally became a first-class librarian on August 18, 1914, at the age of 59. Throughout his career he was celebrated as an exemplary employee of great intelligence and dedication. It is emphasized in all his successive evaluations that he started from a primary education, that he trained himself to reach a level of knowledge (both scientific and professional) at least equivalent to his fellow librarians. Paul Viollet asked he be promoted to librarian in 1904 ; this request was supported in 1908 by a letter to the rector signed by over twenty professors of the faculty, and was finally answered in 1912.

The team he was in charge of during the war consisted of three aides : Antoine Pradel (49 years old in 1914, arrived at the library on March 1st, 1890), Albert Hissler (55 years old in 1914, arrived at the library on October 1st, 1897) and Eugène Brière (53 years old in 1914, arrived at the library in December 1897). Thus, an aging but very experienced team, joined in 1915 librarian Lefeuvre, who had been honorably discharged (he had previously been working at the library since 1911).

Under Viollet’s direction, the division of labor among the various members of the team was well defined : the chief librarian and the librarians were responsible for acquisitions, indexing and ensuring room presidencies during the opening of the library. The most senior aides made copies of the cards drawn up by the librarians to feed the various catalogs and registers, while the other aides were in charge of the entry and exit of the readers (verification of the cards for one, the bags and purses for the other), the communication and storage of the books, the cleaning of the rooms and the dusting of the books.

In relation to these tasks, the impact of war on the daily life of the library is obvious.

Regarding the reception of readers, the hours were reduced due to the elimination of evenings sessions. Most importantly, the number of readers in the library followed the decline in student numbers, which had fallen tenfold in 1915, from about 700 to about 70 readers per day that year. These attendance figures rose again very gradually after 1916, always proportionally to the number of students in the faculty.

Regarding the processing of books arriving at the library, exchanges of thesis with foreign countries ceased almost entirely (only about thirty volumes were received between 1914 and 1918 and none was sent). Exchanges of thesis with the other French faculties did not cease completely but were greatly diminished.

Acquisitions of books fell drastically, from more than 700 in 1913 to 154 in 1915, and around 230-250 per year between 1916 and 1920.

On the other hand, the number of donations fell only for the year 1915, otherwise maintaining pre-war rates, with fluctuations depending on the year.

The overall amount of work therefore decreased during the war years, but the number of agents even more. Due to lack of personnel, the table of journals (a press review of these publications), proudly specific to the library and deeply appreciated by the professors of the faculty, stopped being updated.

Looking at the constitution of collections, the war also seemed to have an important impact.

From a financial standpoint, the budgets were deeply restrained starting in 1914. In order to face the expenditures of 1915, the university was not able to count on State help and had to draw from its own resources, which explains the budget limitations of the entire war period. Starting in 1916, the budgets slowly returned to their usual levels. In parallel, the cost of books rose along with the cost living, notably after 1917. These two financial elements clearly explain the considerable decrease in purchases and donations adding to the library collections around this time : while in 1913 alone, 713 monographs had been bought, only 633 joined the collections for the entire time period between October 1914 and late 1917.

The impact of war on collections was not limited to financial factors. The expensive and inexpensive acquisition channels also underwent changes, linked to the new political configuration. On the one hand, the purchase of books from Germany or Austria-Hungary was subjected to regulations regarding trade with the enemy ; on the other hand exchanges of thesis with foreign countries was suspended.

Indeed, concerning purchases, a decree of September 27, 1914 prohibited any trade with the subjects of the German and Austro-Hungarian empires, and declared null and void, as contrary to public order, any act or contract concluded with them, as well as the execution of these acts or contracts. The August 17, 1915 Act, however, provided for the possibility of an exception, by decision of the Minister of Finance, explained by a memorandum of the Ministry of Public Education on March 16, 1916, to all the rectors and directors of major scientific establishments : the Minister of Finance gave instructions to the customs services to facilitate the importation of German and Austro-Hungarian books and journals of a non-commercial nature, which the establishments would obtain from booksellers in neutral countries, and subjected to the approval of the inspector of book trade. This exception was actually used very sparingly, which is reflected in the library of the Paris Faculty of Law by the purchase of only 24 German books between 1915 and 1919.

The acquisition channels were also more complicated even with allied countries, with the introduction, for example, of a compulsory import license from England, by implementation of the Franco-British Convention of August 24, 1917.

On the side of inexpensive acquisitions, while inflows of donations fluctuated from year to year, but were maintained, even during the war, inflows of foreign thesis constituted before the war the largest inflows, quantitatively, of foreign production in law on the premises of the faculty, and their reception stopped in the last quarter of 1914. The list of beneficiary universities was discussed in the autumn of 1914 within the university board, with the aim of redirecting the copies intended for Germany to Anglo-Saxon and South American countries.

All these elements obviously had not only consequences on the scale but also on the composition of the collections.

No document exists, or at least none remains, compiling a definite documentary policy for the library of the Paris Faculty of Law, which would make it possible to see the evolution of this policy prior to, during and after the war. However, it is possible to analyze the different entry registers of the library. The main register contains a list of all the works entered in the collections and assigns them, indicating the date of arrival, an inventory number and a classification. It indicates the method of entry into the collections, by purchase or by donation, and specifies, for purchases, the supplier and the price, and for donations, the donor (individual or institution, with the name). The library also maintains thesis registers listing thesis received by university and date of defense.

The study of these various registers clearly shows a virtual disappearance of German publications, except in the context of donations, a decline in purchases of foreign works, and a breakthrough in Anglo-Saxon works. All these developments can be explained by the material contingencies mentioned above, but they had very concrete consequences : by analyzing not from the point of view of developments but that of the content, what these records tell us is that over the period of the war, the library of the Paris Faculty of Law only stores and suggests in its collections the sole vision of France and its allies on law. The extracts from the German and Austro-Hungarian press, carefully selected and translated by the War Ministry before being sent to the faculty, do not quite restore a balance.

Thus, the war had consequences on staff, on attendance, on budgets, on collections, and yet, what is striking is that it ultimately did not disrupt the daily life of the library.

What might seem like a paradox has a very simple explanation : Jules Rousselle.

From 1914 to 1918, in addition to his usual duties, Rousselle sat on the faculty’s library commission, drafted annual reports, handled correspondence and managed the library’s daily life.

Viollet’s faithful lieutenant, trained by him, scrupulously followed in the footsteps of his disappeared predecessor. The strong organization that had been put in place was partly muted, but not modified. The reading of the library’s correspondence registers is striking in Rousselle’s quasi-mimicry of Viollet in its formulations. Perhaps revealing of this persistence in pre-war operations is the pursuit of requests for their publications from various institutions. Given the difficulties of the post office or the lack of staff in the library, it seems surprising to see the time and effort devoted to requests sent, among others, to the governors of Senegal, Pondicherry, Saigon, or to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or Trade concerning numbers of missing periodicals that the library wanted to retrieve.

Rousselle also walked in Viollet’s footsteps through the attention paid to the team. One of the main concerns of agents during the war was how to cope with the high cost of living. What compensation they were entitled to or not was the subject of frequent discussions. Evening sessions were indeed paid for, and the problem arose as early as the autumn of 1914 as to whether and how the faculty could compensate for this loss of income. Every year, until the end of the war, Rousselle pleaded in favor of his colleagues and obtained a favorable response from the university, and funds were taken from the Goullencourt pension to be able to pay these bonuses. Among the few archives relating to the library in the 1920s, there was the continuation of these negotiations, with the refusal of the university at the end of the war to continue to compensate for evening sessions.

In 1917, the assistants had also started to receive a cost-of-living allowance (Act of April 7, 1917).

February 1918 and beyond : normalization and evolution

The armistice was not signed until November 1918. Peace Treaties were negotiated and signed between 1919 and 1920, or even as late as 1923 when including the Treaty of Lausanne.

Thus, if 1918 was an important year for the library of the Paris Faculty of Law, with the arrival in office of Viollet’s successor, as will be discussed later, it does not represent more of a clean cut than for the rest of society.

It was very gradually, over a period extending until the middle of the 1920s, that the situation of the library seemed to be normalizing.

The librarians and aides who had been mobilized started returning to the library in 1919.

Attendance figures returned to about pre-war levels in the 1919-1920 academic year, with many students only being discharged in the spring of 1919. The years 1920 to 1922 saw a peak in attendance, linked to the organization of special courses and examinations for discharged students.

Budgets increased slowly until 1923, never returning to the level of 1913, and declined again after 1924. The number of acquisitions returned to correct levels after 1920, but without returning pre-war numbers. Thus, hardly more books were purchased between October 1914 and the end of 1922 (2,301 over more than eight years) than in the three years 1911-1913 alone (2,004).

At the same time, the cost of books, especially foreign books, continued to rise with the cost of living. Developments in acquisitions during the war do not seem to have disappeared with peace, at least until the mid-1920s : records show that fewer German books were purchased, more English ones, and more generally a slight decline in French ones. However, this composition of the collections can largely be explained by the very massive increase of the cost of foreign books and its unpredictability : prices could more than double between the time of ordering and the time of receipt, depending on the price of the German mark or pound sterling.

Despite the discussions held in the autumn of 1914, copies of thesis intended for exchange with foreign universities remained in the universities they were defended in throughout the war after all, and the mentioned return to balance did not take effect : the 21 German beneficiary universities were still barred from exchange after the war, and other universities, notably American ones, were added to the list. Exchanges gradually resumed in the early 1920s and were stabilized around 1925.

Regarding collections, it is striking to note that the weight of current events persisted. If the constitution of a corpus of publications related to the war was the result of a clear will from the library commission as early as 1915, it was without premeditation that a certain number of publications integrated the collections, in connection to the Russian revolution and its after-effects : re-analyses of the French Revolution, works on socialism, Bolshevism, trade unionism, workers’ rights, and the multiplication, starting in 1920, of titles on economic organization, statistics, sociology, economic doctrines, etc.

Finally, the library became a memorial by integrating into its collections an archival collection created at the request of Dean Larnaude, and bringing together publications and memorabilia related to students who had fallen on the battlefield.

While one can speak of normalization, one cannot speak of a return to normalcy for the library. In a somewhat paradoxical way, it was peace and not war that really brought changes to the organization of the institution, with the arrival of Viollet’s successor Eugène Bouvy, who took position on February 1st, 1918. This change was also anticipated and delayed by the faculty, as pointed out by Bouvy himself – appointed by the decree of November 23, 1917 to take up his duties on December 1st, but only taking office three months later – in a letter to the secretary of the faculty of December 22, 1917 : “Je sais qu’il n’y a pas extrême urgence, au point de vue de la Faculté, à ce que j’arrive prendre possession du service, mais, vis-à-vis de l’administration qui m’a nommé, comme vis-à-vis de mon successeur à Bordeaux, je considère comme un devoir de me trouver à mon nouveau poste [I know that there is no extreme urgency, from the point of view of the Faculty, for me to be able to take up the service, but, vis-à-vis the administration which appointed me, as vis-à-vis my successor in Bordeaux, I consider it my duty to take my new position]”.

Without elements on how he led the team, what stands out the most from the transformations made are the changes in the way the library worked and got things done. These changes are particularly visible in the keeping of registers and catalogs, although it should be noted that Bouvy did not make his greatest changes until after Rousselle retired at the end of 1923. For example, if the updating of the table of journals resumed in 1918 at the express request of the professors of the faculty, Bouvy was reluctant, emphasizing that it was not a job provided for in the tasks officially assigned to librarians, and obtained its suspension in 1920, and the transmission of this work in December 1923 to assistants in specialized work rooms under the supervision of Rousselle, who had become a honorary librarian. Similarly, the book entry register of the library was abandoned in its old form on January 1st, 1924 : there was no longer an inventory register on one side and a classification register on the other, the latter being also used as an inventory. In general, there was a recovery of internal work, with a reduction and simplification of the writing work, along with a redevelopment of the premises and a redeployment of the collections.

Thus, the library of the Paris Faculty of Law participated actively in the war, by the mobilization of its staff, and by the constitution of collections that support the professors’ legal war. It adapted to the budgets, the readers, the human, financial, political and legal conditions created by the situation. But war represented more of a parenthesis than a disruption for the library. It postponed the end of the Viollet period, which thus lasted thirty-eight years plus four. Even as a parenthesis, it nevertheless left deep traces and echoed into the Thirties. A last contract was approved by the Commission of repairs at the beginning of 1930 ; it opened an account with a German bookseller in Leipzig for the purchase of books published in Germany, chosen by the commission of the library. Thus, Bouvy had already retired when, in 1930-1931, the largest contingent (over 450 volumes mainly periodicals, of documents supplied by Germany as reparations) arrived at the library.