“Et puis honneur à nos grands morts qui nous ont fait cette victoire ! [And honored be our great dead, who made this victory for us!]”

Georges Clemenceau, Chamber of Deputies, November 11, 1918

Men live.

They also die, sometimes very young and before their time.

Memento mori !

Remember death, the old societies repeated.

Our old masters liked to quote Latin – the authorities and philosophers of our Antiquity.

Death is inevitable, but seems far ahead of us.

But in the heat of August 1914, once war was declared, death did not prowl. It was present, everywhere, often, for those who had gone to the borders to defend the country. As provided for by the provisions of the General Staff since the spring of 1914, Plan XVII entered into force. It was to be implemented at the time of mobilization, the concentration of troops by rail, and the first operations.

Plan XVII ? Previously, since 1875, in view of constraints, international relations and threats, leaders of the French Armies had drawn up the sixteen other plans. In the 17th military region, that of Toulouse at that time, the 34th infantry division was the unit to which many conscripts would converge, even if there were several other units in the city. These men went to the borders in the first days of the war.

To defend the threatened spaces, among the millions of men en route to the Armies in the summer of 1914, those who came from the Toulouse Faculty of Law and the Technical Institute of Law.

We know the battles they fought, the losses they suffered, the cruel mournings. But time has passed, an entire century that has erased the stigmas and closed many wounds.

For many among those men lost their lives. War memorials bear witness to this.

But do we really decipher them, beyond the names they bear ?

Do we know the burden of suffering that lies behind names, forenames, letters engraved in marble, underlined in purple or gold ?

The memory of these men is inscribed in our premises, those of the old faculty bequeathed by the masters and students of yesteryear.

Dead men without borders ?

What borders, anyway ? Land borders ? Not all of them were those of France or Europe.

The fighting would also concern the distant overseas territories, and their maritime spaces.

As early as August, men from the Faculty of Law died for their homeland, swept away by the violent whirlwind of war.

Not all of them were military.

Not all died in France, nor in Europe, nor in uniform.

Raymond Leygue was one of them. Born in 1887 in Muret, he quickly went through the Faculty of Law in 1907-1908. His future did not lie in studying law. In 1914, he became a clerk in the civil services of French Equatorial Africa. The declaration of war was made known there around mid-August – two weeks after the official declaration of mobilization and declaration of war, slow transmission of news in an area with no wireless transmission. At this point, he and a few dozen others believed they could succeed in a surprise attack on a Deutsche Kamerun military outpost on the border of French Congo, on the Sangha River. Opposite, they had seen them coming, and the Germans had withdrawn to better organize and counter-attack. Raymond Leygue, a civilian, was killed with arms in hand on August 22, 1914, to defend the M’Birou outpost taken from the Germans a few hours earlier, very far from the “ligne bleue des Vosges [blue line of the Vosges]” as it was called at the time. Raymond Leygue’s name therefore does not appear on the base built by the Department of Veterans Affairs, General Administrative Office, Memory of Men. This extraordinary tool brought together the name cards of the majority of those who had “morts pour la France [died for France]” between 1914 and 1918, well over one million three hundred thousand men, very few women and civilians among them.

Raymond Leygue was actually the son of one of the mayors of Toulouse. His father – who bore the saame name – Raymond Leygue came from a family of Muret very involved in the political life of the time. He occupied the Capitole de Toulouse from 1908 to 1912. Death reaped everywhere, without regard for social levels.

Thus Toulouse-Capitole University inherited the memory of the old Faculty of Law, but not only.

For there are two war memorials in this area. On one side, spectacular and majestic, the monument to the dead of the law school, two hundred and twenty-four names. On the other side, that of the Technical Institute of Law, a modest marble plaque even if it honors fifty-seven names, thirteen of which were also those of students enrolled in the Faculty of Law.

A radical novelty ?

No, of course not. Dead heroes have always excited the gratitude of the living, the ones heard after the death of heroes.

Thus in one of the inner sanctums, the École Polytechnique, stands a monument honoring the students of the School – under military status since Napoléon I – fallen for the homeland since the first moments of the foundation.

A polytechnician himself – X 1857 –, President of the Republic Sadi Carnot (1837-1894) had inaugurated the monument erected in honor of those killed for the homeland in 1894. This year marked the centenary of the School, as well as the year of the assassination of the President (June 25, 1894). In Toulouse and in the midst of republican pomp, he had presided three years earlier over the opening ceremonies (May 1891) of the buildings of the new faculties of medicine and pharmacy, on the future Jules Guesde alleys.

This is to say that the salute given to alumni, to the gloriously fallen former students, was not an absolute novelty. After the war of 1870, many testimonies were also raised in memory of the sacrifices made by citizens, soldiers, civilians. In addition to the fact that this flowering was diffuse and quite late in relation to the event – we all know the name of La Défense, the easternmost district of Paris. “La défense de Paris”, a monument and bronze collection erected in 1883 to celebrate the efforts of the defenders of Paris in 1870-1871, knew a famous fate. But this flowering was not general, it was not organized in a systematic way. It is true that the Republicans in power would multiply these initiatives of commemoration : for the defeat of 1870, glorious indeed by the sacrifices made, was first of all that of the Empire forever banished.

Associations of veterans of 1870, patriotic societies, municipalities, joined their efforts to raise objects of memory. Thus in 1902 in Montauban, sculptor Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929), an already famous local, erects a monument to the glory of those of 1870 ; much later, the city of Toulouse supported the erection of a monument erected in 1908. Some of these testimonies were completed on the eve of the 1914 war, such as that of Tarbes, or better still that of Carcassonne inaugurated on July 12, 1914, at a time when the aftermath of the Sarajevo assassination (June 1914) had already begun the fires of war.

Four years later, and even before the fighting of the First World War ended, the magnitude of the sacrifices led la Représentation nationale [French Parliament] to plan a national and coordinated tribute. While the overall number of dead and missing was still unknown – an element that was in part a matter of military secrecy – it was known to be large and considerable. Significantly, Dean Hauriou (1856-1929), in a meeting of the faculty council held on December 2, 1918, gave the figure of 124 killed, a figure unfortunately much lower than the reality. On July 2, 1915, a law had already organized the attribution of the mention “mort pour la France [died for France]” on death certificates, both military and civilian, both men and women.

The Law of October 25, 1919 established a framework for action to honor the dead and missing. It would be completed subsequently, without necessarily respecting the provisions set out in the 1919 text. Thus the one which made the Pantheon the sacred depository of the registers where the names of the dead fallen for the homeland would be recorded remained a dead letter. On the other hand, and this promise would be held, the law also mentions the erection in towns of war memorials of which the State undertakes to finance a fraction ; Livres d’Or distributed in the communes and constituted by institutions and bodies, must participate in a national liturgy. On July 14, 1919, a ancient-type cenotaph was raised at the foot of the Arc de Triomphe and saw the Victory parade pass.

Starting in November 11, 1920, the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, under this same Arc de Triomphe, is one of these elements and not the least, lit from November 11, 1923 by the proclaimed eternal flame, and revived each evening during a very codified ceremony. Even under the Occupation, though before the eyes of the occupier, this ritual would be maintained.

The Toulouse Faculty of Law was not, of course, going to stay away from this vast movement.

In each of his first day of class speeches during the war period – it was not yet known that the conflict would be global and of such long duration in 1914 – Dean Maurice Hauriou did not fail to emphasize both the greatness of the spirit of sacrifice, as well as the magnitude of the losses suffered for the just cause. The mark and the memory could not find a better place than in a Livre d’Or that could be leafed through, and later in a monument that states the names of the disappeared.

As soon as November 13, 1918, Dean Hauriou mentioned the constitution of this sacred testimony, the Livre d’Or. We shall not elaborate further here, the subject is dealt with elsewhere. This piece of memory, moving by its simplicity, is preserved in the archives of the university. But it is not the only piece of memory.

The monument remains.

In fact, one should say monuments – plural.

Monuments

There is a plurality of existence. The Faculty of Law was of course the parent institution, and the one with the most staff, though these numbers were not comparable to those of today. We are talking about fewer than a thousand students, around 700 in the 1910s, all preparations and training grouped, all levels combined, against more than twenty thousand today. But it also houses an institution, the Technical Institute of Law. Legally, the Institute is an association declared in 1909, which brought together in the same synergy the law school and the notary school, a structure hosted since the beginning of the century on the premises of the faculty. Some of the Institute’s students were also enrolled in the Faculty of Law. The latter absorbed the Institute in 1924.

The Faculty of Law

As early as August 1914, the war came, and students and former students of both entities found themselves exposed to the fires and misfortunes of war. In short, hundreds of them died. Other students, fortunately the majority, would come home safe and sound, though deeply scarred by their terrible experiences. Here, we mean male students : indeed, no woman is listed among the heroes killed in combat, or fallen victim to these battles within the meaning of the law of July 2, 1915. Already present at the faculty, admittedly in small numbers, very few in fact were potentially and directly in contact with the conflict.

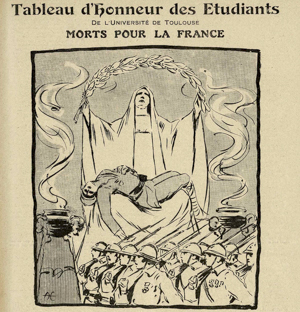

The victory snatched and celebrated, Dean Hauriou would initiate the glorification of the disappeared. Just a few days before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, a “tableau provisoire des morts pour la France [provisional painting of those who died for France]” was inaugurated on June 23, 1919 in the Faculty’s premises, in the presence of the press, which reported the event in its columns.

This painting was not preserved, as it was in sorts melted into the two monuments designed in memory of the dead and disappeared of the faculty and the the Technical Institute of Law.

A decision taken by the faculty council on March 3, 1921 founded the principle of the erection of a lasting testimony of the faculty’s gratitude. One of the projects presented by Toulouse sculptor Jean-Marie Fourès (1870-1926) won. He had presented both, and Sketch B was unanimously selected. The artist, beyond the faculty, had often been selected by municipalities or other institutions for his projects in public commissions around the national religion resulting from the war.

The Faculty memorial was meant to be a “plaque de marbre suffisante pour l’inscription de 200 noms [marble plate sufficient for the inscription of 200 names]” – which is already a violent indication of the bleeding suffered –, “et encadrée dans une boiserie de chêne ciré et au prix de 8 750 F [framed in a waxed oak woodwork and for a price of F8,750]”.

The location chosen for the implantation of this mark of honor is very symbolic. In the entrance hall of the faculty, a few steps from the grand staircase, on the wall placed between the door of the council room and that of the antechamber of the professors’ cloakroom, the program of tribute stands, six meters long and three high. The white marble triptych originally planned was not sufficiently large. It was indeed necessary to add two lateral complements to add surnames revealed ex post. For the war killed more than imagined : eighteen more names were engraved on either side of the main stele, or two hundred and twenty-four in all, each with their first name. Still, some did not find their place because of lack of space, or late arrival of supporting documents, and have remained in the files created during the research intended to draw up this pantheon of the Faculty of Law. Honor to those sixteen missing from the university glories.

The decoration of the monument is sober but imposing, impression enhanced by the shade and dark patina of the waxed oak. Palms, laurels delimiting a space reserved for the display of the list of the killed. A naked sword was placed on the plates of the sales of Themis lying on the ground : Justice and her sword. Justice, like the sword, also punished the German Empire in this fight of law against barbarism. An Adrian helmet is placed on the set. Named after military steward Louis Adrian (1859-1933), designer of this head protection made of steel sheet, this headgear was in use in all units from 1915 when the “blue horizon” uniform was adopted. The martial dimension was thus given.

Above the triptych, a simple inscription in golden letters, “A LA MÉMOIRE DES ÉTUDIANTS DE LA FACULTÉ MORTS POUR LA FRANCE MCMXIV-MCMXVIII” [To the memory of the students who died for France 1914-1918]. Below the inscription, on eight columns, the alphabetical list of those who “died for France”, except the case of the eighteen identities transcribed on the two side marble plates.

The Technical Institute of Law

The testimony is much more modest and sober.

There is certainly the white marble plate ; the arrangement in columns ; the names and surnames engraved, fifty-seven in all, but in red letters ; the dedication, but different from that of the Faculty of Law, “A LA MÉMOIRE DES ÉLÈVES DE L’INSTITUT TECHNIQUE DE DROIT MORTS POUR LA FRANCE 1914-1918” [To the memory of the students of the Technical Institute of Law who died for France 1914-1918]. Beyond that, no ornamentation, no decorative program that would distract the eye.

The commemorative plaque was placed on the premises of the former Institute and was moved during construction work on its premises. It is now affixed in the main entrance of what was once the Faculty of Humanities, currently TSM, the Toulouse School of Management.

Names engraved in marble

Honor to them, they have been dead for a century.

What to discover behind the terrible parade of names and surnames ?

That the notoriety of the Toulouse Faculty of Law then largely drained the large space that is today that of the Occitanie region. From this comes the vast majority of students who have known what is known as the Belle Époque, the Beautiful Era, that before 1914 and its war. This area of recruitment is not surprising, considering that the Montpellier Faculty of Law was not reestablished until 1878. Hence the forced choice of Toulouse for the age classes born before the 1880s, and the reasoned Toulouse choice of the younger generation faced with the novelty of this Montpellier settlement at least until 1890. Hence the many presences coming from the department of Hérault. In metropolitan France, Paris and its area were also represented. The colonial empire (Algeria, Tunisia, etc.), whose children would so often shine during the fighting, also provided its contingent of students, a small minority.

That the vast majority, three quarters, died in combat, a great novelty compared to previous conflicts. Military fevers previously decimated troops before they fired a rifle or saw the enemy, even from afar.

That two thirds of the dead of the faculty were killed in the two years 1914 and 1915, seventeen months of fighting in which the blood of men was not spared : excess offensive was the dominant virtue and value for many leaders on the brink of war.

That the majority of those killed (42 %) were officers, captains for the highest rank ; a proportion slightly higher than that of non-commissioned men, soldiers and corporals (38 %).

That death struck along the litany of battles, that of the borders and the Marne in 1914 ; that of the Somme in 1915 ; of Verdun in 1916, etc. Almost all lost their lives in France and Belgium. But others died in Germany, prisoners of the enemy, or in Africa as Raymond Leygue did in August 1914.

That the vast majority of those killed were young men, between twenty and thirty-five years old, which of course corresponds to the classes first and most mobilized. Some of these defenders of the homeland were quite not twenty years old, such as Charles Pradel de Lamaze, class of 1896, who died in gunfire at age 19 on January 5, 1916. Others, only few, were in their late forties – officers : Émile Baron, captain in the 341st Infantry Regiment, class of 1868, fell on September 7, 1914 during the First Battle of the Marne.

Absence ?

This commemoration desired and organized by the academic authorities of the Faculty of Law was not the only one on the university premises. Originally devoted to the study of law, they were also devoted to humanities, after the inauguration (1891) of the brand new faculty, adjoining the law school.

Upon the return of peace, the Faculty of Humanities also wanted and built a monument in honor of its students. It brought it along when it left the rue Lautman premises in the late 1960s. For in the purest tradition bequeathed by the ancients, the remains and remembrance of the dead follow and must follow the destiny of the living as they depart from the theater of their first existence. They were transported to their new home. Thus, the monument to the memory of those killed in the Faculty of Humanities is awaiting resettlement in the modernized and transformed premises of Jean-Jaurès University. Was the latter, a former teacher of this very faculty, not, moreover and of course, one of the first victims of this conflict ?

Any other absences ?

Off the faculty premises, rue Lautman, formerly rue de l’Université, was so named to honor Albert Lautman, professor at the Faculty of Letters, officer in 1939-1940, escaped prisoner, resistance fighter, arrested, deported and finally executed on August 1st, 1944.

On the other hand, almost nothing in the premises celebrates the memory of the combatants of the other world war, that of 1940.

A lone, lonely plaque, affixed by the care of the Association of the sons and daughters of the war killed of Haute-Garonne. Stripped with a tricolor border, it honors Jacques Reverdy, killed in action on June 9, 1940.

Another, posted a few years ago by the National Federation of Resistant and Patriotic Deportees and Interned, recalls the sacrifice of those who fell in the dark years.

The disaster of 1940, lived as painfully as its aftermath, did not give the faculty the will to transcribe in marble everyone’s sacrifices.

Students died so that France would live on : some under the flags of the regular units ; others executed by the occupying forces, such as Georges Papillon.

A law student in 1940, gone into hiding, wanted by the services of Vichy and those of the occupier, he was arrested by the Nazis on August 16, 1944 and shot the next day, almost on the eve of the Liberation of Paris.

A vanished memory ?

The testimonies of former students of the 1960s are unanimous. At the time of their training at the faculty, the laying of wreaths ; the speeches delivered ; the magnified remembrance of the alumni who died under the flags, were no longer on the program of the solemnities of the faculty.

The defeat of 1940 may have had something to do with this abandonment.