In 1913, during the solemn opening ceremony in November, the dean, Charles Jacquier, presented his report and praised the successes of the Catholic Faculty of Law in Lyon, particularly the consistency of its student numbers. He does not yet know that six years will pass before the next solemn opening ceremony, with the Great War sweeping across France a few months later and disrupting the lives of teachers and students alike.

On the eve of the war, the organisation has hardly changed since its beginnings. It should be noted that the Catholic Faculty of Law was inaugurated in November 1875, two years later appeared the Catholic faculties of humanities and sciences, thus allowing the use of the term Catholic University to describe all the faculties. In accordance with the law of July 12, 1875 establishing freedom of higher education, the establishment of three faculties thus authorised the use of the term “university” and the creation of a mixed examination jury, offering students of the Catholic faculties the opportunity to take their exams before a jury composed of half professors from state faculties and half professors from free faculties. Catholics in Lyon quickly took advantage of the new law, as did other cities, with Catholic faculties also being established in Paris, Lille and Angers. However, from the outset, these Catholics in Lyon faced competition from the establishment of a state Faculty of Law in November 1875. Thus, the ideological challenge of the Catholic Faculty of Law is clear: it aims to provide legal education in accordance with Christian values, whereas the state faculty seeks to convey republican values. This ideological struggle explains the republican legislation, five years later, aimed at limiting the influence of Catholic faculties. The 18 March 1880 law did indeed weaken the Catholic faculty in Lyon, which lost both the benefit of mixed juries (introduced two years earlier only) and the authorisation to use the term “university”.

In 1913, after several decades, the operation remains practically unchanged and the Catholic faculties are still under the direction of the bishops. Various advisory councils exist: the rectoral council, the academic council and the faculty council, but the central pivot is embodied by the rector: this is the 5th rector, Monsignor Fleury Lavallée. The first rector appointed by the bishops was Abbé Louis Guiol between 1877 and 1884, followed by Monsignor Jean-Louis Carra until 1894, then Pierre Dadolle until 1906. Finally, Monsignor André Devaux succeeded him as the fourth rector, before being replaced upon his death in 1910 by Monsignor Fleury Lavalée, who remained in office until 1945. As the true head of the institution under the authority of the bishops, the rector presides over the various councils, signs and promulgates internal regulations, ensures discipline, supervises teaching; he may also make final decisions on the admission or expulsion of students. He presents his candidates for the positions of vice-rector, deans and vice-deans to the bishops; the same applies to the secretary general and the list of candidates for tenured professorships. Each faculty has a dean; in 1914, the Faculty of Law is headed by Charles Jacquier, who succeeded Henri Beaune in 1906.

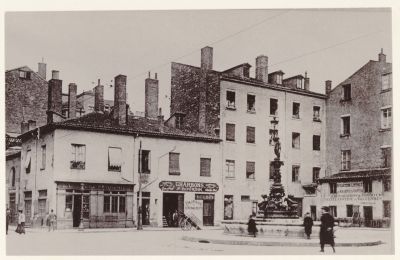

While the institutional structure remains unchanged since its inception, another sign of conservatism is more tangible: the buildings have also remained unchanged since the first classes. Students are still based in the modest building on Place Saint-Michel (since renamed Place Vollon), and it isn’t until the end of the First World War that a new building, the Hôtel de Cuzieu on Rue Sainte-Hélène, becomes home to the Catholic Faculty of Law.

Concerning the professorial staff, here too the evolution is moderate. For the academic year 1913-1914, there are 14 professors (compared to 10 originally), plus one lecturer, Emmanuel Gounot, who is also a former student of the Catholic Faculty of Law in Lyon. The young lecturer has just completed his doctorate at the Faculty of Law in Dijon (first part in legal sciences, then second part in political sciences). It should be remembered that since 1880 and the loss of mixed juries, students at Catholic faculties are forced to take their exams at state law faculties. Some, like Gounot, fearing the bias of the state Faculty of Law in Lyon, a rival of its Catholic counterpart, choose other state faculties further away. It is difficult to know whether this feeling of injustice was real or imagined, but Paul Brac de La Perrière (first dean of the Faculty of Law), based on the results of the 1877 examinations (one year before the effective establishment of mixed juries), regretted the difference in the number of failures in Lyon and Grenoble. According to the dean, in 1877, only 1 in 10 candidates failed in Grenoble, compared with 4 in 10 in Lyon (session of August 15, 1877, register of rectoral council sessions kept in the archives of the Catholic University of Lyon).

The continuity of the professorial staff is evident, as a number of them have been there since the beginning or almost since the beginning, embodying the pillars of the Faculty of Law. This is the case for dean Charles Jacquier, but also for vice-dean Alexandre Poidebard, professor of international law André Gairal de Sérézin, economist Joseph Rambaud, as well as Sébastien Wies (civil law) and Gilbert Boucaud (commercial law). Likewise, André Mouterde has been there practically since the beginning, holding a chair in civil procedure since 1877. The longevity of the teachers at the Catholic Faculty of Law is noteworthy, as many of them teach for more than 40 years. Joseph Rambaud teaches for 45 years, and in tribute to his longevity, the Catholic faculty decides to name the chair of political economy after him in 1923.

Beyond presenting traditional law courses to students (similar to those offered at state faculties), these professors also promote Christian values in lectures aimed at a wider audience than just students. These are the conférences du vendredi, which exist since 1878. These weekly lectures, held every year between January and April, involve all the Catholic faculties, with different teachers taking turns to participate, and are open to auditors. Women are also admitted, as the aim of these lectures is to attract as wide an audience as possible, which seems to have worked, since it is estimated that between 200 and 300 people attend each year. For the year 1913-1914, two professors from the Faculty of Law gave lectures: Auguste Rivet on the stages of the confiscation of religious property and Sébastien Wies on ‘Simon Renard, ambassador of Charles V, and the marriage of Mary Tudor’.

Let us turn our attention to the student population: the Catholic Faculty of Law in Lyon had 104 students on the eve of the First World War. This represents a very slight decrease compared to the previous year, for which dean Jacquier reported 115 students; however, it should be noted that there has been a significant increase since the beginning in 1875. It should be remembered that when it opened, the Catholic Faculty of Law had only 73 students and 10 chairs. However, this number of students remains modest when compared to that of the Catholic Faculty of Law in Paris during the same period, which numbered more than 400 students. In perspective, the state Faculty of Law in Lyon also had a much larger student body: 585 students on the eve of the war. The limited number of students at the Catholic Faculty of Law in Lyon also raises questions about its survival when war breaks out.

Nevertheless, one aspect has changed significantly since the beginnings of the Catholic Faculty of Law, namely the curricula, which have become considerably more intensive. Catholic law faculties, and the one in Lyon is no exception, have adapted to national reforms. Indeed, the Catholic Faculty of Law was forced to adapt its programmes to bring them into line with those of state faculties – this in order not to penalize students who, let us remember, are assessed exclusively by teachers from state faculties since the abolition of mixed examination juries. As a result, the curriculum, which had focused mainly on the study of Napoleonic texts, was gradually replaced by a more diverse range of subjects with various reforms of legal studies between 1877 and 1907. In 1875, first-year courses focus on Roman law and civil law. In the second year, civil procedure and criminal law were added to the teaching of these two subjects. Finally, in the third year, the programme focused on civil law, commercial law and administrative law.

Various innovative courses then begin to appear in law faculties (both Catholic and public). This is the case from 1877 onwards with political economy, followed three years later by the history of law and private international law. Political economy is then moved to the first year in 1890, before also being taught in the second year in 1907. Constitutional law then appears in the bachelor’s degree programme, initially in the first year under the title “Elements of constitutional law and the organisation of public authorities” in 1889, then under the title “Constitutional law” in 1907. Finally, in the third year, the number of options increases, greatly mobilizing the professorial staff, before a significant reduction in 1895.

The Catholic Faculty of Law in Lyon was essentially a small provincial faculty on the eve of the Great War. Its number of students remains moderate, with around a hundred, but it continues to operate and pursue its activities. In terms of evolution, the only notable changes were the diversification of teaching and the broadening of opportunities towards administrative and political careers, with the introduction of various public law courses, which certainly constituted the most significant change at the Catholic Faculty of Law in Lyon since its inception.

Myriam Biscay, lecturer in legal history, Jean Moulin – Lyon 3, Centre lyonnais d’histoire du droit et de la pensée politique (Lyon Centre for Legal History and Political Thought)

Bibliography

Biscay Myriam, « L’instauration des jurys mixtes : l’exemple lyonnais de la Faculté catholique de droit », dans Revue d’histoire des facultés de droit et de la culture juridique, du monde des juristes et du livre juridique, vol. 39‑40, 2019, p. 899‑925.

—, « Les conférences publiques des facultés catholiques de Lyon : l’enseignement d’un droit chrétien, instrument d’une propagande de défense de l’Église », dans Les Études Sociales, vol. 173, no 1, 2021, https://shs.cairn.info/revue-les-etudes-sociales-2021-1-page-27, p. 27‑50.

—, « Le combat des facultés catholiques face à l’enracinement de la république (1880-1914) », dans Cahiers Jean Moulin, no 10, 2024, https://journals.openedition.org/cjm/2901.

—, « Les facultés de droit catholiques : des armes de propagande au service de l’Ordre Moral », dans Olivier Dard, Bruno Dumons (dir.), L’Ordre Moral 1873-1877 : royalisme, catholicisme et conservatisme, Paris, 2025, p. 269‑280.

Gaudin Cédric, Les Facultés catholiques de Lyon (1875-1885), Mémoire de maitrise d’histoire contemporaine, soutenu à l’université Lumière Lyon 2 sous la direction d’Étienne Fouilloux, 1999.

Moulinet Daniel, « Regard sur l’histoire de la Faculté de droit », dans Revue de l’Université catholique de Lyon, vol. 31, 2017, p. 29‑36.