Despite being a pioneer of higher education with its auditorium and the lectures of Ausonius ( ? 310-394) in the 4th century of our era, Bordeaux had to wait a long time before the opening of its first official university. A rich city and major trading port, it only became a place of legal education during the 15th century with the creation of the Universitas Burdiagalensis. Its structure remained substantially the same for nearly 350 years before being swept away by revolutionary impulses. The city produced many renowned jurists such as Nicolas Boerius (1469-1539), Bernard Automne (1574 ?-1666), Étienne Cleirac (1583-1657), Abraham Lapeyrère (1598 ?-1690 ?), or even famous member of parliament Charles Louis de Secondat, baron of La Brède and Montesquieu (1689-1755).

In Bordeaux as in many other places, the Revolution of 1789 led to the disappearance of the teaching of law. It was necessary to wait for the law of Ventôse 22 Year XIII (March 13, 1804), promulgated a few days before the Napoleonic Code, for the teaching of law to resume, in principle. It should be noted that teachers were required to comply with the Code. Moreover, the decree of September 21, 1804 established the list of the lucky dozen cities which could accommodate these new faculties. A major absence : Bordeaux. Several reasons can be given for this “oversight”, cloaked, for some, as revenge against a rebellious city, for its ties with the English, for its staunch opposition to the mountain perspectives, etc. However, never did the city’s officials lose hope in the creation of a law school in Bordeaux throughout the 19th century, setting in motion all the resources at their disposal.

Many pitfalls awaited them on this path. Their hopes were all too often swept away by a setback under the blow of a fortune that was decidedly not very favorable to them.

I. Disappointed hopes

Following the abolition of the two law schools of Bordeaux (one of canon law, the other of civil law), the opposition began to organize in 1804 when it was revealed that the decree reopening the faculties left the city aside. The movement was organized under the leadership of two lawyers : Joseph-Henri Lainé (1768-1835) and Philippe Ferrère (1767-1815). They considered it unthinkable that such a city should be deprived of a teaching as noble as that of law. Although they failed to convince the government, the town hall was paying attention.

Nevertheless, finding a representative was proving difficult at a time of great change for France. The succession of regimes, and thus of ideologies as regards higher education and its development, proved to be powerful obstacles.

It was not for lack of opportunities, however, and the goal was approached on a number of occasions. It was for example the case with the arrival in the government of Minister of Public Instruction Salvandry (1795-1856) in 1838, who was in favor of a denser university network in France. The same year, he allowed the opening of a science faculty and a humanities faculty. He was quickly replaced. His successor did not share his vision, and the hopes of a law faculty for the Aquitanian capital were smashed again.

In 1840, a new hope arose : Villemain (1790-1870), who was Salvandry’s friend, took over the ministry of public education. A rather affable man, he allowed the evanescent idea of a probable creation to arise, stimulating a vigorous effervescence in the legal circles of Bordeaux. Petitions were started by the Chamber of Notaries and the Board of the Bar Association, with the certainty that this would be the coup de grace giving concrete expression to their expectations. The city went to war, creating a commission to lead this project. Nevertheless, its case once again remains in the limbo of oblivion. The cause ? This law faculty would have overshadowed the existing ones in Toulouse and Poitiers.

These critical failures eventually got the better of a seemingly unwavering determination. To add on bad luck, the authoritarian phase of the Second Empire again forced the city to postpone its project due to other more urgent concerns. It should also be noted that the city’s late support for the Empire caused a lot of suspicions. Prefect Haussmann (1809-1891) thus exiled anyone suspected of rebelliousness, and the institutional disorganization that reached Bordeaux dried up the soil that could have led to the establishment of a new law school.

In 1864, Mayor Henri Brochon (1810-1974) breathed in a new wind. Soon, the Academic Board joined the request of the municipality, quickly accompanied by the General Council of Gironde. Émile Fourcand (1819-1881), who would become a Bordeaux town councilor, drew up a report pointing out the gap between the large number of legal practitioners in Bordeaux and the lack of a training center for legal subjects. The result ? A new categorical refusal from the ministry.

Reflecting a renewed tenacity, and wishing to take advantage of the liberalization of the regime, a new request was made in 1867, seeking the support of Charles Zevort (1816-1887), the newly invested rector, who was very much in favor of this creation. Convinced of the benefits that the city could derive from this faculty, he recruited five lawyers to the bar so that they could begin offering free public courses between 1869 and 1870. The town council, aware of this significant step forward, took these lessons under its patronage.

At the same time, the city requested a new, more complete report, responding more acutely to the concerns expressed by the Minister of Public Instruction, the conclusions of which were delivered on February 5, 1869. This time, the exact costs of construction, operation, or even the prospects of profitability in the short term were presented. Like other applicants for a law school, Bordeaux used examples of cities that were smaller in size but still generated profits – like Douai, a creditor in its first financial year. The facts were presented abruptly and trivially, but the arguments seemed convincing. Convinced that the circumstances were now in their favor, aided by the beginnings of law courses given by Bordeaux lawyers, deputies – notably Mr Amédée Larrieu (1807-1873), whose name was eventually given to a square of the city – harassed Paris to finally obtain the final blow.

The last obstacle that stood in their way was the Minister himself, who also happened to be the dean of the Poitiers Law School. Uninhibited by this concurrence of facts, the applicants pushed to the point of reminding the Minister of the importance of leaving aside his personal preferences for the salvation of the public interest, which imperatively demanded the opening of the long-awaited establishment. By chance, political instability pushed the Poitevin dean out of power, in favor of a substitute who was more inclined to lend them an attentive ear.

Before this barely ajar door could close, the city decided to break it down at the ram, playing its most powerful card at the most opportune moment, during the town council of February 7, 1870 : Bordeaux solemnly and officially undertook to acquire at its own expense the land for the construction of the faculty, to carry out from its own resources the work necessary for the construction of the building, and to defray all operating costs, including staff costs.

On April 25, 1870, Rector Zevort wrote to the Mayor of Bordeaux to inform him that the process was gaining credibility with the government. Galvanized, the city then made ever-increasing, almost indecent commitments, in its deliberations of July 11, 1870 : in addition to the costs of construction, maintenance, and staff, it formally undertook to return for 12 years ( !) the surplus of its operating budget to the State – following the promises made by other cities with similar claims.

This time, the case seemed well made, the promises difficult to dismiss. The city was seeing the light after half a century of patience. Fate, ever unpredictable, decided otherwise when the Battle of Sedan broke out, leading in its wake to the fall of the Empire. The Republic was declared on September 4, 1870, less than two months after the culmination of a case that was about to be finally accepted by the previous regime. The request was thus returned to the sidelines.

Nevertheless, in its misfortune, a boost was finally given to the Gironde capital : a delegation from the National Defence government took refuge in Bordeaux at the end of September. Perhaps did they discuss this project with the local elected representatives, and managed to convince Jules Simon (1814-1896), then Minister of Public Education who remained in Paris, of the need to open this faculty. Legend claims that the decree of December 15, 1870 authorizing this creation, reached Bordeaux in a hot-air balloon released by Paris, which was being besieged by the Prussian army.

In the backdrop, the trauma of this military defeat affected the academic organization. As early as 1867, Ernest Renan (1823-1892) pointed out the interest that a nation should take in its universities, quoting the victory of Prussia over Austria, which had been permitted by its scientific advancement. In 1870, many scholars rallied to Renan’s cause : they considered the rich and powerful German universities to be the cause of the French debacle. Louis Liard (1846-1917) even saw it as a mark of the development of German patriotism, shaped by shared science. At this point, in France, the reform of faculties stopped being a simple matter of science, but a matter of the ties between the French, ties that had to be rebuilt and strengthened.

Thus Sedan became the catalyst of the unease of the French elites in the face of German science. It now seems obvious that they wanted to rebuild our universities, diversify our faculties, render unto them their former greatness, in order to find in them the promise of a moral revenge on the victor of 1870.

At any rate, whatever the causes mentioned before, Bordeaux was now virtually authorized to create its faculty. All that this institution needed to do is to find its fulfillment in the construction of a physical building.

II. The chaotic construction

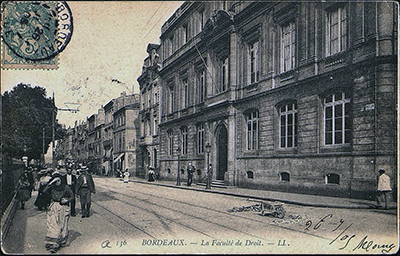

As early as 1869, the city began to consider a location for its planned faculty. With several places in the running, the choice fell upon an area located on the place Pey-Berland, opposite the cathedral. Once the location had been established, the work shortly began, following the decree of December 1870.

As promised, the city used its own funds to finance the works, helped by the generosity of Charles Fieffé de Lièvreville (1791-1857) who, upon his death, bequeathed the city of Bordeaux 600,000 francs, 300,000 of which in real estate assets. Thus, the financial sacrifice made to the Government by the city was not really theirs. Architect Charles Burguet (1821-1879) then offered plans and a quotation in May 1871, which were immediately accepted. Thus, work began in August of the same year.

At the same time, temporary but formal courses were being offered under the name of the new faculty. Without premises, the lessons were spread in different halls all over the city. This highlights an umpteenth obstacle : there were already 200 students, and the future faculty was being built for a maximum operating capacity of 300 people. This new awareness of the size of the building to come caused a sudden stoppage of the construction site, giving Charles Burguet time to issue new plans on December 16, 1871. Once the administrative obstacles were overcome, the structural barriers came : the building was located on marshy grounds, very close to the Peugue, a stream crossing the city. Burguet, by adding another floor to his original plan, made the building as a whole heavier, and the foundations needed to be stabilized more firmly, in consequence of which contractors were given the right to cancel their tenders in response to the additional costs involved.

These difficulties delayed the project, and on March 8t 1872, the Budget Committee of the National Assembly took the opportunity to abolish the Bordeaux Law School altogether, then bogged down in difficult construction work, although it had been teaching courses for two years. Thanks to this last argument, the committee reversed this unfortunate decision.

Aware that its project was on the brink of collapse, the city decided to urgently resume construction of the building, negotiating increases with the craftsmen in the face of the difficulties encountered. All agreed, except one – though the matter would be settled in court five years later. The construction work could resume at the cost of a heavily modified estimate – the initial 150,000 francs budget now amounted to 208,000.

After many twists and turns, the construction was completed without any problems, and the final stone laid on August 11, 1874. Untraditionnaly, the inauguration had already taken place on November 20, 1873. Reportedly, Dean Couraud’s speech (1827-1892) was far, far too long. Infused with references in Latin, waltzing between speech and law lecture, the intention was nevertheless good, calling for the opening of new teaching chairs and supporting his request by offering the demonstration of this imperative necessity. But, carried away by his own lyricism in evoking the legal history he began to ask philosophical questions such as “What is Law ?”, and to answer them, to the great displeasure of his audience, whose patience was running thin.

The newspaper did not fail to point out the intricate beauty of the facade. The interior, on the other hand, was much less refined, not to say bleak : not even the minister’s visit in 1876 garnered any sort of embellishment. Sculptor Dumilâtre (1844-1928), father of the Monument des Girondins on Quinconces Square, had been approached, but nothing was finalized. The dean complained to the director of higher education of the Ministry of Public Education who, in a spirit of generosity, granted him two statues : one of Montesquieu, the other of Cujas. There again, the matter was not a sinecure, as the statues were not delivered at the same time. It also turned out afterward that no bases had been provided on which to place them : the two busts lay on the ground… until 1882 !

III. The stormy institutional life

This long-awaited, desired and hoped-for faculty had to be the new flagship of Bordeaux higher education, especially in response to the additional costs generated by the changes in plans mentioned. The city, which had borne all the expenses, had to demonstrate to its taxpayers that the money has been used reasonably. The press played an important role, with the newspapers praising this majestic building, proudly standing in front of the cathedral on the place Pey-Berland. But it was its usefulness that needed to be imprinted, and the local press bored its readership senseless with statistics about student attendance or library use.

A contradiction with Dean Couraud’s opening speech can be of note here. Indeed, the man himself complained about the absenteeism of the students – which can be explained by the great dryness of the exegetical lectures then given in the amphitheaters. Nevertheless, he boasted of the good performance of his students, while supporting the idea that they could be much better if families were fully aware of the need to regularly send their children to attend the classes of the faculty. It is also interesting to recall that one of the reasons given for supporting the construction of this new place of education was to allow young people to remain close to their families, thus avoiding the expensive journey to Paris, which was, after all, the capital of all vices. By trying too hard to prevent young people from moving away from the family nucleus, they no longer even bothered to go to the place Pey-Berland !

The law school encountered many other waves, this time in its courses. In 1876, the city of Bordeaux, with its faculty of humanities, followed an innovative movement by opening a chair of geography. Moreover, the sections in place in 1886 continue to be joined by new disciplines such as art history and archeology, which are no longer under the wing of the history department. Psychology and then sociology emancipated themselves as well from the guardianship of philosophy.

The greatest earthquake came from the first course in social sciences by Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) in 1888. Was this new science to be considered a field of humanities or law ? A very thorny subject that pits Gabriel Baudry-Lacantinerie (1837-1913) – dean of the Faculty of Law – against Alfred Espinas (1844-1922) – dean of the Faculty of Humanities– at the Board of Faculties on July 17, 1888. It was heard, specifically, that “the dean of the Faculty of Law points out that by definition and by essence, social science belongs exclusively to the field of legal studies. The dean of the Faculty of Humanities insists instead on the difference between the science of societies and the art of the jurist”, proof of the exacerbated conflicts around this field. Humanities was eventually granted this victory.

Behind this petty rivalry lay a nebulous competition, which is echoed at the Sorbonne : the same type of dissension arises, and the main motivation of lawyers to appropriate the subject is none other than their thirst to fully enslave the social sciences to the teaching of law ! If proof were needed, we might simply recall that, immediately after the abandonment of this project by the Parisian Faculty of Humanities, the Faculty of Law no longer upheld any claim to a chair in social sciences…

Law and sociology would meet, however, first under the impetus of Durkheim who, in his inaugural speech, strongly invited lawyers to attend his lectures. Léon Duguit (1859-1928) – who was also a friend of Durkheim – pointed out at the meeting of the Law School on 9 December 1887 that the course schedule of the sociologist coincided with another course in law ; it was therefore necessary to find a compromise between the two faculties in order to avoid this overlap, without the course in social sciences flying the flag of legal science. A sign of victory for this desired diversity, the faculty board of 1889 highlighted the meeting between lawyers and sociologists : law students and professors both attended Émile Durkheim’s courses.

Finally, the issue of premises came up again. In 1898, the dean began to complain about the small size of the building. In 1899, the examination copies kept since the opening of the faculty were destroyed to free up space. Once again, the city had to acquire premises near the faculty with the idea of enlarging it. It was proposed to buy the adjoining building, at the corner of rue du Commandant-Arnould and the place Pey-Berland, which only happened in 1907. Still too cramped, the eyes turn to rue Cabirol, a complicated choice. Indeed, this area belongs to the Church, and for an expropriation procedure to be able to be put into action, it is necessary to demonstrate its public utility. The eponymous decree did not arrive until 1910, and the buildings on rue Cabirol were acquired by the town hall in 1911. Work began in 1913, just before the Great War interrupted this umpteenth project… which did not resume until 1920 !

In short, if the faculty was not a war field in the literal sense, its creation was a constant struggle. Everything stood against it, successive governments, entrepreneurs, deans, and even the river Peugue itself – very expensively so ! This was only a foretaste of the internal struggle that this institution would have to go through in the face of the great conflict of 1914.

Alexandre Frambéry-Iacobone, A.T.E.R. IRM-CAHD (University of Bordeaux)

Bibliography

Brémond Kevin, Une histoire politique des facultés de droit ; l’image des facultés de droit dans la presse quotidienne d’information nationale sous la troisième république (1870-1940), thèse droit, université de Bordeaux, 2018.

Cadilhon François, Lachaise Bernard, Lebigre Jean-Michel, Histoire d’une université bordelaise : Michel de Montaigne, faculté des arts, faculté des lettres, 1441-1999, Talence, France, Presses universitaires de Bordeaux, 1999.

Clavel Elsa, La faculté des lettres de Bordeaux (1886-1968). Un siècle d’essor universitaire en province, thèse histoire moderne et contemporaine, université Michel de Montaigne, 2016.

Malherbe Marc, La faculté de droit de Bordeaux : 1870-1970, Talence, France, Presses universitaires de Bordeaux, 1996.

Poux Ludovic, La construction des palais universitaires de Bordeaux au xixe siècle, thèse histoire contemporaine, université Michel de Montaigne, 1993.