“In the life of a faculty, as in that of a family, events repeat themselves, almost always the same, which are the most numerous and the most necessary. Sometimes new events occur, bringing about a modification, small or large, in their organization and operation. Those are necessary as well, but they must not be too frequent, lest they bring about too great an instability into an existence whose continuity and regularity are, in a way, the fundamental principle. The life of bodies, as that of families thus includes happy and unhappy events alike. Would it really be life otherwise ?” ; these remarks were expressed by Dean Ferdinand Larnaude in 1921, in the annual report on higher education institutions of the Paris Academy (law school). Larnaude, who had been dean since November 1st, 1913, still observed the consequences of the war on his institution at the time he wrote these lines. An institution that actually spent the war period clinging to its normality, without being able to escape the effects of events.

Before the war, the daily life of the Faculty of Law of Paris had been embodied by an administrative and pedagogical organization, a building, professors, administrative and library staff, teachers, students, all governed by regulations, traditions, history.

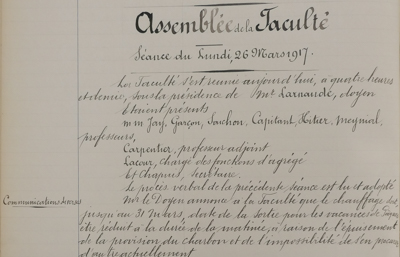

Thus, the faculty was presided by Dean Ferdinand Larnaude from November 1st, 1913, until November 1st, 1922. The two decision-making bodies of the faculty were the board and the assembly. The board managed disciplinary issues, proposals for vacant chairs, and budget through the validation of annual accounts and especially the complete management of the faculty’s legacies and foundations. The assembly managed educational and scientific matters. Above the faculty, the University of Paris board, under the direction of the vice-rector, decided the budget for all the higher education institutions of the capital, had the last word on the attributions, modifications and maintenance of Chairs, and was the place of development of a common policy for the academy’s institutions, especially in the field of international relations, and one of the places of discussion of national policies.

In 1914, the faculty was comprised of forty-five tenured, assistant or associate professors for an audience of about 8,000 students, a team of ten people in the library, from the chief librarian to the hall boys, and at least twenty people for the administration and maintenance of the building, from the secretary of the faculty to the janitors.

The academic year usually began around November 10. The majority of students were enrolled either for a bachelor’s degree or for a capacity certificate. The bachelor’s was obtained in three years, the capacity in two. To ensure student attendance, a system of non-cumulative enrollment was put in place, that had to be renewed in person four times a year. Students who were not up to date with their enrollments were not allowed to take the end-of-year exams. The classes were annual, with finals in July. Resits were organized in late October and early November. The teachings include both the courses themselves and optional lectures, given by professors, assistant professors and associates of the faculty. Students were charged yearly to attend these lectures, which brought practical exercises to bachelor level and went deeper into doctorate-level questions. Each year, the most deserving bachelor students were invited to participate in the end-of-year competitions, with two competitions at every bachelor level, plus a national open competition for third year students. PhD students, apart from the thesis prizes, could also take part in the doctoral competition, and apply for various competitions organized and prizes awarded by the faculty.

For the most part, this state of affairs persisted during the war : the faculty did not move ; the dean remained in office (he was even re-elected in 1919) ; the board and the assembly of the faculty continued to meet regularly to validate the timetables of courses, the dates of re-entry and examinations, the subjects of courses and conferences, to approve or not the proposals for free courses, to vote on the budgetary accounts each year and to manage the annuities and investments of the faculty ; the courses were professed, the conferences given, the diplomas issued ; the various end-of-year competitions organized by the faculty were maintained. Both the library and the seven specialized work rooms continued to function and accommodate students and external readers.

However, this persistence was ensured only by constant adaptations to the reality created by the war. And while these adaptations were seen as transient, some proved to be lasting.

Adaptations

The Paris Faculty of Law did not move and was not invaded during the war. There were, however, two periods, in August-September 1914 and in the spring of 1918, when a rapid entry of German troops into Paris was feared. With this in mind, the faculty took certain measures of its own initiative, as well as following received instructions.

Even though the rector’s office requested at the beginning of September 1914 that all of the precious collections (paintings, sculptures, archives, manuscripts, rare and precious books) be secured and sheltered, they had been inventoried, removed from their usual places of storage, and placed in boxes in the cellars of the faculty since as early as the end of August. Above all, the faculty needed to know how to react to a fire, which was the most important risk considered ; training in this direction was provided by firefighters, who also provided written instructions to be distributed. As the faculty was not equipped for this risk, the appropriate equipment had to be acquired.

Since the threat was clearly reduced after the end of 1914, it was observed that when, in order to cope with the shortage of paper, the rector’s office approached the faculty in 1916 to find out whether it had any waste paper for sale, it was notably these famous stocks of firefighters’ instructions that were sold to the highest bidder.

However, the anguish returned in the spring of 1918 with the last pressing manoeuvrings of the Germans. This time, the faculty prepared for the bombing and evacuation of Paris : the cellars were requisitioned by the authorities as shelter for 1,100 people in the event of bombings, with assistance provided if necessary by the police outside and by volunteer supervisors inside the building. Posters announcing these measures were put up in the faculty. Although the bombings did reach Paris, the faculty was spared, and the order to withdraw from the capital, although flittingly mentioned, was never given.

Another material consequence was that, as early as September 1914, the State finances were redirected to support the war effort. The rector’s office and then the ministry successively sent instructions to the faculties to stop all expenses, and even canceled orders that could still be canceled. In 1915, since the State did not participate in the budget, the Paris Faculty of Law could rely only on the university’s finances and its own resources. From 1916, the State began investing again, although very modestly, increasing its subsidy gradually from year to year ; even by 1920, it had not yet returned to the level of 1914, even though the high cost of living meant that all equipment at that time cost about thrice as much as before the war.

These conditions forced Dean Larnaude to implement a policy of strict savings, notably by drastically reducing the library’s budget. The issue of heating, the price of which was rising dramatically, became a recurrent and increasingly acute problem. In the winter of 1916-1917, the rector requested the reduction of lighting expenditures to an indispensable minimum. Until the Easter holidays of March 1917, the library and teaching schedules were thus reorganized to be concentrated on part of the day, and the courses were moved, grouped in the new buildings, in order to have to use only one boiler.

The faculty’s own resources took a crucial importance. They, particularly through the Goullencourt Fund, made it possible for the faculty to continue to pay their annual allowances to administrative and library staff, to pay cost-of-living compensatory allowances from 1917 to staff not included into the state’s plan, to pay the salary of the assistant in charge of the material organization of conferences, to continue to ensure the maintenance and enrichment of specialized work rooms, but also to involve the faculty in successive national loans to support the war effort.

One of the characteristics of this period was the impact that the decisions of ministries other than the Ministry of Public Education had on the life of the faculty ; starting with the orders of incorporation.

The first mobilizations began in August of 1914, and the consequences on the public of the faculty were enormous : from about 8,000 students enrolled during the year 1913-1914, the figure fell to just over 1,000 for the year 1914-1915, and it was not until the years 1920-1921 that the numbers returned to pre-war level. These figures lead us to nuance the idea of normality preserved in the daily life of the Paris Faculty of Law. Courses and conferences were maintained, but the students were few and far between on the benches. Similarly, mobilization affected the faculty in a relatively important way. Half of the library’s staff (five out of ten) were enrolled as early as August 1914, and at least ten members of the administrative staff were also called up. However, the library and the administration managed to maintain a regular functioning, sacrificing the non-essential.

Ultimately, it was the teaching staff who were the least affected by enrollment, simply because the vast majority of teachers were past the age of mobilization. Out of 45, in addition to Hitier, who volunteered in August 1914, only five were called, and only two spent the war in the military : Maurice Bernard, a tenured professor, hired as a pilot, died in 1916 during an exercise. Allix, also tenured, at the beginning of the war, was first under-lieutenant-commissioner reporting to the 105th Division of Infantry, then to the 133rd Division, then to the entrenched camp of Paris. However, the Ministers of War and of Public Instruction issued a memorandum on September 11th, 1915, enabling mobilized members of education to exercise their professionnal duties during their military time-off. Therafter, provided that they were granted the Minister’s authorization, mobilized professors were allowed to teach. Thus Demogue, Jèze and Percerou, with this authorization, spent the entire period of the war without leaving the Paris Faculty of Law and Allix, transferred to Paris, was able to join them at the beginning of the 1918 academic year. This provision was not a privilege for Parisian professors : Brunet, a professor in Aix, mobilized in Paris, gave the Paris Faculty of Law a doctoral conference in political science in the second half of 1918-1919.

All these elements seem to explain quite easily how almost all of the courses and conferences continued to be provided throughout the war period. Still, reality was more complicated.

Before the war, about 50 courses and a dozen lectures were dispensed each year at the faculty of law in Paris for the courses of capacity certificate, bachelor’s degree and doctorate, with in 1913-1914 a contingent of 45 tenured, assistant and associate professors. Three professors were mobilized, called, or volunteered of their own volition. In addition, Professor Geouffre de La Pradelle was on a propaganda mission on the American continent for most of the war, and three professors of the faculty (in turn) were sent each year for several months to oversee the exams at the French School of Law in Cairo. If we add to these absences the deaths of five teachers – Massigli, Cauwès, Renault, Thaller and Audibert – between July 1916 and July 1918 (they did not die in combat), a total of nine teachers, a fifth of the body, ended up missing. In these conditions, it is surprising to note that only two courses really went down the drain during this time period : administrative law (litigation and finance), a doctoral course with a specialization in legal science, and statistics, a doctoral course with a specialization in political and economic science.

Courses and lectures were actually maintained, on the one hand by a permanent game of musical chairs, and on the other hand by the arrival of colleagues expelled from their universities by the war : Professors Lacour and Lévy-Ullmann, of the Lille Faculty of Law, received tenure at the Paris Faculty of Law for the duration of the hostilities, by effect of the ministerial decree of October 27, 1916. Professors Bourcart, Carré de Malberg, Rolland, and the lecturer Oudinot, of the Nancy Faculty of Law, received temporary tenure at the Paris Faculty of Law from March to December of 1918.

Thus, the Paris law school was far from spared by war. In the final count, its Livre d’Or lists nearly 700 names of students, alumni or staff members who died on the battlefield. Furthermore, for the entire duration of the war, death was omnipresent in the daily life of the faculty. As early as September 1914, regularly updated paintings with the list of the dead of the faculty were hung in the entrance on rue Saint-Jacques, a constant crossroads for students, professors and staff. When the 1916 academic year began, an area was reserved in the library for memorabilia sent by families of their loved ones dead in battle. At the end of each year, starting in 1915, the bachelor exams began with participants and the faculty assembly standing, listening as the dean listed the former laureates who had died on the battlefield. To this can be added the litany of names, of dead ginned up throughout the meetings of the Council and the faculty assembly : Hervé Maguer, library assistant, in August 1914 ; Paul Viollet, head librarian, in November 1914 ; Professor Massigli in July 1916 ; Professor Maurice Bernard in October 1916 ; Professor Cauwès in April 1917 ; Daniel Bellet, in charge of free courses, in the summer of 1917 ; Rector Louis Liard in the summer of 1917 ; Professor Renault in February 1918 ; Professor Thaller in March 1918 ; Professor Audibert in July 1918 ; Professor Beauregard in March 1919 ; Rector Lucien Poincaré in March 1920. And although some teachers were past the age of being drafted, their sons were not. Thus, in the litany of names quoted in the discussions, can also be found the sons of Professors Audibert, Bartin, Beauregard, Bourguin, Deschamps, Gide, Leseur, Massigli, Meynial, Pillet, Planiol, Saleilles, Thaller, all dead in the field of honor.

To pay tribute to all its disappeared, other than through the provisional paintings in the Grande Galerie, the faculty took steps from 1914-1915 to gather memories and documentation, and its efforts led on the one hand to the creation of an archival collection kept in the faculty library, and on the other hand to the publication of a Guest Book and the erection of a monument to the dead, in the entrance hall on the side of rue Saint-Jacques, in 1925.

Evolutions

Taken in the midst of war, the “vielle maison” (a nickname given to Sorbonne university, meaning “old house”) tried to maintain its course and resist certain adaptations brought about by circumstances. This was especially the case with the introduction of special schemes for mobilized students.

Although a special examination session was organized in mid-September 1914, it was one of the few actions put in place until 1917. Until then, the faculty and higher administration both were reluctant to take measures for a particular class of students, referring to block solutions in the post-war era. But, under pressure from Parliament, the ministry and the rector’s office had to prepare for it, and in March 1917 they asked for proposals on possible adjustments to the various faculties. The Paris Faculty of Law appointed an internal commission at the end of March 1917 to report on the subject, and in passing listed some of the questions to be asked : wheter to implement changes in the number of tests, in the programs, in the modes of examination ; wheter to organize sessions to pass the diplomas more quickly. The commission’s report was presented by Capitant in May, and a lively discussion took place from May to the end of June. Critics focused on the idea that these measures would introduce inequalities between students in the traditional stream and those in the special system, and the risk of creating discounted degrees. Resolutions were nevertheless adopted and forwarded to the rector.

The question rebounded, in slightly different terms, at the start of the 1917 academic year, following a ministerial memorandum ordering the provision of special education for the 1919 class, so that they had passed their examinations before they were incorporated in April 1918 – which had been refused to the 1918 class. The faculty decided to set up a specific course exclusively geared towards students with a bachelor’s degree or a capacity certificate, over one semester. Each teacher was free to determine in their own course the essentials to be taught in this first semester, the complementary classes to be taught the second, even if the programs had to be determined from the outset. However, beyond the proposals voted in June 1917, this organization was what survived in the later provisions.

In fact, the decree of January 10, 1919 regulating the educational situation of students serving in the armed forces, in addition to authorizing cumulative enrollment and organizing four exam sessions per year (January, March, July and October), introduced reduced curricula along the lines of what had been done for the 1919 class. A capacity certificate could thus be obtained in one year, and a bachelor’s degree in eighteen months.

This particular organization for demobilized students was the last great challenge brought by the war to the faculty. The curriculum for the 1919 class was renewed for the 1920 class. The first deferrals and demobilizations in 1919 led to the first special exam sessions, mainly from October 1919, accompanied by lectures for demobilized soldiers, aimed at providing accelerated preparation for the examinations. The 1920-1921 academic year was the busiest, with nearly 9,500 students, and more importantly over 14,000 examinations. There was no way, in 1920, to cope with these numbers by calling on professors from provincial universities, as was the case in the past. For the first time, a ministerial decree allowed the recruitment of ordinary law doctors as auxiliary examiners. This provision was highly appreciated and extended for the following years. This, however, was not enough to face the cohorts of 1920-1921, so the Paris Faculty of Law received the help of 18 provincial professors, in addition to the eleven adjunct doctors. Among these doctors, a new body would become institutionalized : that of assistants. There were eight in this first year, seven men and one woman, funded by the university board. The faculty had based its request on its needs for examiners, but they were in fact assistants for the specialized working rooms and for the professors in charge of them.

Finally, a particular group of students among the demobilized was the American students. There were 450 enrolled in the Paris Faculty of Law from the end of March to the end of June 1919. They were given five special courses in French, every other class a lecture in English to explain and evaluate. Eight professors provided these courses and lectures.

This measure was part of a constant concern throughout the war : how to attract foreign students to France to fight against competition from German faculties ? The idea of a legal war carried by the French faculties induced the need for the widest and most effective dissemination of French civilization and science. In addition to propaganda through the official and unofficial ties between faculties, and through the circulation of professors and their publications, questions on the best way of bringing foreign students were thus raised from the beginning of 1916. A commission was appointed in 1917 at the faculty to draw up a report on the subject, and new types of courses were introduced in 1919, with diplomas acquired over a semester.

The Paris faculty of law thus endured through the Great War via continuity, adaptation, and evolution. Daily organization and traditions were maintained. The formal start of year ceremony, with distribution of prizes to the winners, was even reintroduced in 1921. But under this façade, the faculty emerged deeply scarred by the war. First by the heavy human cost it paid, then by the changes in the organization of its teaching that had to be assumed and integrated, reluctantly, in part, for the program modifications ; with pleasure for the assistants. Since the war had permeated society as a whole, one of the developments it brought about at university was almost unconscious : from the end of 1918 onwards, the introduction of a school booklet for each student was mentioned ; the individual university booklet was finally introduced from 1920, and the administration wished to make it clear that it must “be in a format similar to the military booklet”.

Alexandra Gottely