Even before the signing of the armistice with Germany, the University of Lyon had entered fully into this movement characterized by the efforts of civil society, in order to convert military relations between allied nations into cultural exchanges that were hoped deep and fruitful. The Alliance thus sought to renew itself, while deepening itself, since one would strive to access facets hitherto totally unknown or little known to the culture of yesterday’s military ally. In short, it was hoped that the temporary fraternity of arms would be converted into a solid friendship, which would, however, be lasting only if each made the effort to know the other better. It was American academics, grouped within the American University Union (AUU), who, even before the end of the war, drove this movement. It would lead French universities to welcome, sometimes massively, demobilized American student soldiers, awaiting re-embarkation for the new world. Having obtained, in December 1917, General Pershing’s agreement in principle, the AUU had put itself in contact with the National Office of French Universities and Schools, in order to consider the conditions of this temporary reception.

Asked to do so in June 1918, the University of Lyon, despite fears that it could not easily accommodate its American guests, nevertheless welcomed this request. Like all its counterparts, it had been preoccupied since the end of the 19th century with the concern of weakening German academic influence. So the prospect of capturing, for the benefit of France, this American student clientele who, until 1914, had looked mainly towards Berlin had a sweet scent of revenge and intellectual victory. At the same time, it was obsessed with the development of its own international influence and was working on it in 1918 in the form of a propaganda work, the writing of which was entrusted to professor of the faculty of humanities Auguste Ehrhard. This arrival of American student soldiers was therefore a golden opportunity to become better known across the Atlantic.

In the end, far fewer than expected (430 instead of the thousand initially announced), the American student soldiers who arrived in Lyon in the spring of 1919 were nevertheless met with a warm welcome. The Faculty of Law received about a hundred of these students for whom it had designed a quarterly program of special courses, some of which were taught directly in the English language : Criminology (J. R. Garraud), Introduction to the Study of Law (Edouard Lambert), Political Economy (René Gonnard), International Commercial Law (Maurice Picard), History of Treaties (M. De Saint Charles). However, what characterizes the law school of Lyon is that it went beyond this brief moment of encounter with the American youth. Far from being an ephemeral impulse, quickly regressed after the re-embarkation of American student-soldiers, the conviction that the alliance concluded during the war with the Anglo-Saxon world should be prolonged and deepened by institutionalization, became for the entire duration of the inter-war period one of the engines of the scientific action of the Lyon faculty. In the register of symbols, it has largely inspired the policy of granting honorary doctorates, awarded in particular to English professors Lee, Gutteridge, Buckland and their American colleagues, Garner, Brown-Scott and Wigmore. In a much more institutional and sustainable context, this same conviction enabled Professor Edouard Lambert to achieve an already long-standing aspiration : the creation of the very first French Institute of Comparative Law, which still bears his name today, and the establishment of a Chair for the Study of International Peace Organizing Institutions, intended to promote the “spirit of Geneva”.

The birth of the Institute of Comparative Law

Throughout the conflict, Edouard Lambert had obviously adopted a position of withdrawal : he had kept complete silence, contrasting with the very committed patriotic remarks made by the majority of his colleagues in Lyon. The Great War had, it is true, represented a very painful ordeal on a private level for a professor who had lost his eldest son, declared missing in action in June 1918, and a nephew, to whom he was paternally attached, killed in March 1916. But everything suggests that the conflict had reinforced more than ever a long-standing commitment to promote the study and teaching of comparative law. It had already been nearly twenty years since the legal historian had extended his interests to this young discipline, then in the process of being formed. In 1900, on the occasion of the great International Congress of Comparative Law held in Paris on the sidelines of the Universal Exhibition, he had made a remarkable report devoted to the general theory of this nascent discipline as well as to the method which should be his own. A few years later, he had seized the opportunity that the extensions of his resignation from the Khedivial School in Cairo had finally presented. For the young Egyptian nationalists, many of whom had come to Lyon to receive the teaching of a master who had demonstrated his sympathy for their cause, Lambert had set up the Oriental Studies Seminar in 1908 ; both by his innovative pedagogical methods and by his scientific interests, the latter already foreshadowed the Institute of Comparative Law whose post-war climate would allow the full flowering.

In comparative law, Edouard Lambert already saw in 1900, as he obstinately would until his last breath in 1947, one of the privileged instruments of rapprochement between peoples. Scrutinizing foreign legal systems was already a way to get to know each other better. But Edouard Lambert didn’t stop there. It assigned to comparative law the humanist and universalist mission of overcoming the technical divergences of each legal system, in order to highlight the fund of common rules of the various nations. To insist on what brings us closer together, rather than on what separates us, was also to pave the way for the constitution of international solidarity and why not, in the very long term certainly, to provide the conditions favorable to an international harmonization of law, which by its nature brings peace. In the aftermath of the armistice of 1918, it was first in the direction of the legal systems of former allies, Italy certainly, but above all Great Britain and the United States that Edouard Lambert wished to establish a bridge. He had explained this at length in a voluminous document entitled L’enseignement du droit comparé. Sa coopération au rapprochement entre la jurisprudence française et la jurisprudence anglo-américaine [The Teaching of Comparative Law. Its cooperation in bringing together French jurisprudence and Anglo-American jurisprudence]. This report, drafted on behalf of a committee comprising, in addition to Edouard Lambert, Paul Huvelin, Jean Appleton and Emmanuel Lévy, was submitted to the faculty council. It was a real programmatic article and, as such, it was published in the Annales de l ‘Université de Lyon, while waiting to be the subject of a separate brochure.

To better convince his local and national interlocutors of the need for this creation, Lambert had argued that the international attractiveness, after which French law faculties as a whole sighed, implied an expansion of law education programs. In this world of increasing exchanges, they could no longer be viewed from a national prism that was too narrow and far too dry, especially for the American youth who sought a global vision of the law of the old continent. He pointed out, moreover, that before the war, German university jurists had well understood this need to think much more broadly about law and that this was the key to understanding the attraction that German universities had once been able to exert across the Atlantic. With the recent codification of their civil law, German professors had succeeded, very abusively for the author, in presenting themselves both as the quintessence of the law of European countries and as its most modern expression. Edouard Lambert also played the card of prosaism by showing that a city such as Lyon, turned to international trade, had to have a law school having understood the need to train young lawyers able to render their future employers services by their ability to dispense with foreign legal rules. But the ultimate aim was nonetheless to furnish the future League of Nations with the lineaments of an authentic common law. This would emerge only after an obstinate work of comparison between these two major legal blocks formed by common law and continental law of which, according to Lambert, French law, and not German law, was the matrix.

Supported enthusiastically by his colleagues in the faculty, the project still benefited from two valuable supports : that of Alfred Coville, former professor of the Lyon Faculty of Humanities become director of higher education and that of the parliamentary representative of the Rhône and mayor of Lyon, Edouard Herriot. This latter support was all the more valuable as it was likely to relay Lyon’s aspirations to national authorities. In 1921, Herriot also took the lever of action that was his function as rapporteur of the budget of the Public Instruction to, finally, give the dreams and efforts of Edouard Lambert a beginning of realization. We were certainly far from the three chairs – comparative history, comparative civil law and comparative commercial law – which, ideally, would have met the expectations of the professor. But the Institute of Comparative Law was created by a decree of August 9, 1921 and consolidated two weeks later by the creation of a chair of comparative law on which Edouard Lambert was quickly appointed and to which he would be faithful until his retirement in 1936.

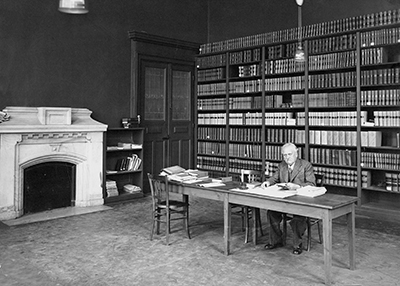

The most difficult task still remained to be done, for it was indeed to a true institute of comparative law, and not of comparative legislation, that the Lyon professor aspired. The title has its importance and it speaks well of the ambitions of its founding father. Edouard Lambert, like many of his colleagues in Lyon, was convinced that the true life of law, whatever its national roots and whatever the part, more or less great, conferred according to the traditions to the legislation, does not lie in the latter, but in jurisprudence. It was readily qualified by both of them as living law. It was therefore for the confrontation and the rapprochement of French and American jurisprudence that the Institute of Comparative Law had declared to want to work in the first place. The ambitious intellectual goal that Edouard Lambert assigned to his young institute, however, risked remaining at the stage of the declaration of intent if a library was not quickly established that could provide students and teachers with access to the largely unknown continent that was then American jurisprudence. He was quite convinced of this, when he declared that the library is to faculties of law and humanities what the hospital is to faculties of medicine or the laboratory to faculties of science. However, it is not excessive to say that he started from nothing. Given that little attention had been paid until then to what did not come from Germany, the local instruments of work did not have the smallest beginning of English or American collection. And it was evident that neither the university library nor the law school had at their disposal at the end of the war the large financial means which the constitution of expensive Anglo-Saxon legal collections implied. On the side of the faculty, the collapse in the number of its students during the previous four years had caused it to lose a large part of its financial resources. As for the university library, it was dependent on ministerial subsidies, which promised to be scarce and meager in this immediate post-war period dominated by so many other emergencies.

If the acquisition of the very first collections of American law was possible in a fairly short time, it was thanks to the bequest of 3,000 francs that one of the former students of the Faculty of Law, fallen in battle, had granted him. Notary by profession and released from all his military obligations in 1914, Félix Balaÿ had made the choice to subscribe to a voluntary commitment at age 49. A lieutenant in the 26th Infantry Regiment, he had died of his wounds on July 18, 1918, not without going through the pain of losing his son, Pierre, a student at the Lyon Faculty of Law, killed three years earlier. Related to the famous Mangini dynasty of entrepreneurs and philanthropists, Félix Balaÿ had been a member of the Society of Friends of the University of Lyon. As such, he could not ignore the importance to the dynamism of academic institutions of bequests and donations granted to them and he had remembered this when drafting his will on the front. The financial necessity in which the faculty was then involved was intertwined with the concern for a strong symbol : this donation, made by a “soldier of law”, a victim of war, was put at the service of a project which, in its own way, intended to work for the construction of international peace through law. This first fund created thanks to the Balaÿ bequest could not cease to be enriched thanks to public subsidies, but also thanks to other donations. Some, in money, came once again from members of the Society of Friends of the University ; others could be made in kind, such as this donation of a large English legal encyclopedia, made by Professor Gutteridge on the occasion of the awarding of his honorary<doctorate in 1926.

With the creation of its pioneering institute of comparative law, the Lyon Faculty of Law had positioned itself as an institution carrying the ideal of peace through law. His aspiration to support the work of the League of Nations quickly manifested in the creation, under the aegis of the International Labor Office, of the Compendium for International Labor Jurisprudence, to which several Lyon professors (Edouard Lambert, Paul Pic, François Perroux) contributed. In the 1930’s, mayor of Lyon Edouard Herriot, to whom Edouard Lambert was so indebted, had to reinforce this now well-publicized vocation to promote peace through law by proposing, and obtaining, the creation of an original university chair : the chair of international institutions of peace organization studies.

The creation of the chair of Peace

Peace through Law… The idea was nothing new in 1919. It had already been debated throughout the 19th century and it was carried, among other pacifist movements, by an eponymous association, born in 1887 in Nîmes, whose last pre-war congress had moreover taken place in June 1914 in Lyon. Although the hope of peace through law had been greatly undermined by the war, which had shown the extreme fragility of this legal bulwark and the contempt for law shown by belligerents, it had paradoxically emerged consolidated by the first world conflict. The idea that it would be appropriate, when guns had finally gone silent, to form an association of civilized States for the defense of law had spread to the various countries of the Entente and, in its wake, had emerged the project of an international organization capable of ensuring the maintenance of international peace.

This last project was powerfully relayed by the famous Fourteen Points of American President Woodrow Wilson (speech of January 8, 1918), who had placed it at the heart of the negotiations at the Peace Conference. The latter eventually gave birth to the League of Nations, whose pact adopted on April 28, 1919, was incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles.

The League of Nations thus created met French expectations with regard to its spirit and its goals. It was driven by the desire to extricate itself from the old system of balance of power between States and sought to secure perpetual peace for the future on the basis of a new idea of collective security, set forth in article 10 of the Covenant, according to which, as the security of each of the Member States became the concern of all the others, military aggression could trigger a collective deterrent, ranging from economic and financial sanctions to armed intervention against the perpetrator of disturbances. But what French activists blamed on this young international organization was the weakness of its means of action, which they had well understood risked paralyzing the institution. While its designers had wanted to promote international arbitration and the search for conciliation for the peaceful settlement of disputes between States, they had not made them systematically binding. Moreover, the French request for the creation of an international armed force, likely to come to the aid of a state suddenly attacked, had been rejected by Anglo-Saxon negotiators.

However great the disappointment of the French militants of the League of Nations was in 1919, they had nevertheless done so against bad luck and firmly believed in the possibility of improving the new international organization, presented by them as a very perfectible starting point. To promote the “spirit of Geneva” and raise French public awareness of the need to strengthen the means of action of the young international organization, the many associations that supported it very classically undertook conference tours throughout the country. This was notably the case in 1929, in order to push French public authorities to sign the general act of compulsory arbitration which had been proposed in September 1928 by the general assembly of the League of Nations. It was in the Théâtre des Célestins in Lyon, full to the brim, that on February 10, 1929, Edouard Herriot, member since 1918 of the council of the French Association for the League of Nations, delivered the inaugural conference of this campaign of action.

Less traditionally, the MP-mayor of Lyon had, the following year, the novel idea of relying on local university resources in order to make his work more sustainable by means of a teaching specifically dedicated to the organization of international peace, which he wanted to be accessible to the general public wishing to train in the notions of European and international solidarity. “Nous avons une école de guerre, pourquoi n’aurions-nous pas une école de paix ? [We have a school of war, why should we not have a school of peace?]” essentially declared the mayor of Lyon to the municipal council during its meeting of August 4, 1930. Edouard Herriot had easily obtained the agreement of the communal assembly and, a few weeks later, the financial support of the general council of Rhône was acquired. It is true that the project represented for the city of Lyon, so close geographically to Geneva, an opportunity to become an original university center, dedicated to the productions of the League of Nations and its subsidiary institutions and, more broadly, specialized in the analysis of international facts.

The following year, the project took the form of a university chair in the study of international peace-organizing institutions, which people of Lyon took the habit of calling the Chair of Peace. Conceived as a provisional position, awaiting his tenure, for a young associate belonging to one of the four orders of aggregation, its financing by the local authorities was guaranteed for a period of 20 years. Its first and only holder was to be a young associate from the 1926 competitive exam for the history of law : Jacques Lambert, the youngest son of the professor of comparative law. Inaugurated on November 14, 1931, this chair held, in fact, a hope that the international events of the following years and the congenital weakness of the League of Nations would quickly destroy. From 1939 onward, it was devoid of its holder, stuck on a mission in Brazil and, in fact, died during the period of the Occupation.

The tragedy of these years of repeated world war and the futility of the efforts made before its outbreak did not, however, succeed in undermining Edouard Lambert’s deep faith in the virtues of comparative law as he had conceived and practiced it. The old professor, whose physical faculties were weakened after a recent heart attack, was always ready to take back his pilgrim’s staff and to fight the concerns of those who were seized by doubt, such as Harald Mankiewicz. In October 1945, to the former secretary of his Institute of Comparative Law whose German origins and anti-Nazism had forced to take refuge in China, then in Canada, he had Ramón Xirau, the new secretary of the Institute whom the Spanish Civil War had fortuitously procured for him, write the following :

“Sans doute le développement de la conception humaniste de la science du droit peut paraître plus compliquée (sic). Mais cela reste le propre de la conception française du droit comparé […] Rien ne se fait en un jour et le propre des traditions de l’Institut de droit comparé est de croire en la réalisation de l’humanisme juridique, malgré toutes les pratiques momentanées auxquelles il se heurte. Il importe de recouvrer cette foi… [No doubt the development of the humanist conception of the science of law may seem more complicated. But this remains the characteristic of the French conception of comparative law […] Nothing is done in a day, and it is characteristic of the Institute of Comparative Law’s traditions to believe in the realization of legal humanism, despite all the momentary practices it encounters. It is important to recover this faith…]”

Catherine Fillon, Professor of Legal History (Lyon III University)

Bibliography

Deroussin David (dir.), Le renouvellement des sciences sociales et juridiques sous la iiie République – La Faculté de droit de Lyon, Paris, Éditions La Mémoire du Droit, 2007.

Fillon Catherine, « La Faculté de droit de Lyon et ses étudiants égyptiens : une délicate expérience pédagogique, entre opportunité politique et opportunisme universitaire », Traverse. Zeitschrift für Rechtsgeschichte – Revue d’Histoire, no 1, 2018, p.72-84.

Fulchiron Hughes (dir.), La Faculté de droit de Lyon, 130 ans d’histoire, Lyon, Éditions Lyonnaises d’Art et d’Histoire, 2006.

Guieu Jean-Michel, Le rameau et le glaive : les militants français pour la Société des Nations, Paris, France, Presses de Sciences Po, 2008.

Lambert Edouard, « L’enseignement du droit comparé, sa contribution au rapprochement entre la jurisprudence française et la jurisprudence anglo-américaine », Annales de l’Université de Lyon, Nouvelle série, II Droit-Lettres, 1919, p.1-118.