Summer 1914 : it is war

Before the start of the academic year in November, only the summer French courses for international students were disrupted by the outbreak of war in August. This summer school took place in two sessions, one in July and the other in August, in Boulogne-sur-Mer. In the summer of 1914, 216 students were enrolled. The courses covered literature, French civilization, phonetics, grammar, style, reading, conversation and translation. Of the 143 students enrolled in the July session, 69 were English, 35 were German, 14 were Russian, 7 were Austrian, 5 were Hungarian, 4 were Swedish, 2 were Dutch, 2 were Canadian, 2 were French, 1 was American, 1 was Colombian and 1 was Finnish. The secretary of the society of patronage of foreign students, who wrote his report for the summer of 1914 after the end of the conflict, recalls the hospitalization of a German student, whose expenses were paid by the society during the academic year 1913-1914. The president of the society had gone to his bedside to bring him strawberries. He wonders if he survived the fighting. The August session only had 26 participants. Many had canceled their registration, while some of the teachers had been mobilized. German, Austrian and Hungarian students in particular had to return to their countries in a hurry. International academic exchanges were dynamic before the conflict ; warfare undermined more peaceful practices.

The University of Lille during the occupation

Lille was occupied from October 1914 on, after suffering terrible bombardments during the siege. The city was cut off from the rest of the country for four years. Throughout the war, the University found itself in a very different situation from other French universities, on the one hand because of the constraints imposed by the occupier, and on the other hand because the classes were not mobilized : the young bachelor students remained in Lille in the autumn of 1915.

Some teachers managed to return to Lille before the occupation began, unlike others who had gone on vacation to other regions. Those mobilized or mobilizable in the autumn of 1914 who had not yet joined the military were evacuated for fear of being requisitioned by the German army. Some of the university staff was concerned. However, many of the students who spent the summer in Lille did not manage to escape in time.

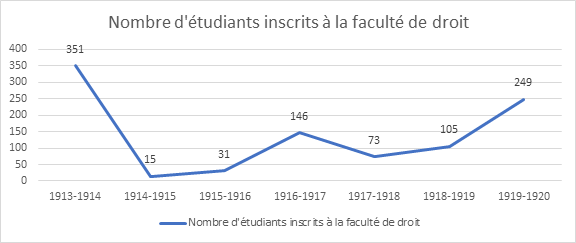

As early as autumn 1914, the Faculty of Law had to reorganize after the mobilization of part of the teaching staff. Only 4 out of 16 professors and 14 students remained. Eustache Pilon, dean of the faculty, was mobilized. The beginning of the occupation saw the premises of the faculty requisitioned by the German army.

The four remaining professors shared the courses : Louis Vallas taught civil law. Jules Jacquey taught international and constitutional law. Paul Collinet, professor of Roman law, also took charge of the history of law courses, while Charles Mouchet took charge of some of the Roman law classes. It was necessary to replace the members of the faculty who represented it on the university board (the dean and Professor Albert Schatz). René Demogue, the dean’s assessor, was transferred to Paris on November 1st. Collinet and Mouchet were elected to sit on the university board, and a decree of the prefecture named Mouchet assessor of the dean.

After a period of stupor and uncertainty, classes resumed in February 1915. The courses of the Faculty of Law were held on the premises of the Faculty of Humanities. Exams were still organized during the year 1914-1915. The report noted that the board had shown leniency towards the candidates in view of the difficult studying conditions and the anxiety generated by the situation. The next academic year began on November 3, 1915, the usual date for the time. Teachers were keen on ensuring operation continuity. The main argument put forward is that the continuation of even a few courses made it possible to facilitate the recovery and to guarantee the future of the institution. A moral argument was also put forward : there were fears about the effects of idleness on young bachelor students who had not been mobilized. Maintaining a “French” intellectual and cultural life appeared to be a form of resistance to the occupier. The annual report also noted an influx of female students in science and humanities aiming to become teachers.

The faculty’s student population increased to 31 students for the year 1915-1916. There were still only four teachers. Three legal practitioners agreed to provide additional courses : François Henri Dejamme, a civil court judge, taught civil law, Henri Dieudonné Prudhomme, a judge as well, also taught criminal law, and a lawyer named Labbe taught commercial law.

The courses resumed, but the war was still present on a daily basis and making the university work proved difficult. Professor Alphonse Malaquin, author of the annual report on the state of higher education in Lille, noted that :

“Placed very close to the battle line, since the trenches faced each other but a few miles from the city, the inhabitants frequently hear the clashing of battle, sometimes even projectiles fall in the neighborhoods of the city ; the planes fly over the streets, engage in fighting, are greeted by intense cannonade ; the convoys, the troops, the vehicles crisscross its streets, reminding the contingencies of reality of the spirit which would like to escape the obsession and the sight of the enemy.”

The material constraints were strong in that the German military post had requisitioned the premises of the law school, the board rooms and the large amphitheater. The laboratory of the physics institute was put at the disposal of a German officer while the pharmaceutical laboratories were requisitioned for the needs of the chemical research of the German army. The Saint-Sauveur Hospital was also requisitioned. The activities of the Faculty of Law were hosted by the Faculty of Humanities, which also housed the classes of the lycée Faidherbe, which was deprived of its premises. Requisitions involved all kinds of products such as coal, paper or fuel. The city experienced shortages of food and coal for heating.

On January 11, 1916, the explosion of an ammunition depot near the university district came to worsen the situation. The windows of the Faculty of Humanities building were broken, doors torn off, partitions collapsed. The floor of the art history institute burst open. Other buildings were affected and many scientific instruments were damaged. In September 1916, three bombs caused further damage to the building of the Faculty of Humanities.

During the winter of 1916-1917, the shortage of coal worsened and jeopardized the functionning of the university. In order to preserve stocks, the German authorities decided to close the school premises as part of a rationing policy. However, the rector obtained that the courses could continue if they were organized on private premises, which were therefore not heated solely to provide the courses. Thus he placed his own house at the disposal of the faculties. Classrooms could only be used again in April 1917. The academic hotel, where the rector resided, was destroyed in a bombing in August 1917. During the war, the German army requisitioned all metal items : the heat plates of the radiators, the lamps (except those of the library), the scales.

The year 1917-1918 saw the imposition of restrictions on circulation between Lille, Roubaix and Tourcoing by the German army. Professors and students may not benefit from derogatory passes for university activities. In order not to penalize the students residing in Tourcoing, an extraordinary examination session was organized, the professors ensuring their organization benefiting from an exceptional authorization to move between the two cities. The examiners took into account the constraints imposed on students who were unable to attend school and were only able to work on the the books borrowed before the travel bans. As for the premises, in 1918, the prefecture was requisitioned and the Faculty of Humanities was put at the disposal of the prefect. The institute of mathematics then housed the Faculties of Humanities and Law but was in turn requisitioned a few weeks later. Literary and legal experts no longer had any premises and had to improvise.

Forced evacuations and hostage-taking

The forced evacuations and hostage-taking of civilians by the German army were among the most traumatic events for the population. Teachers and students were also involved.

The first wave of forced evacuations began in April 1916. Part of the population of the city was evacuated to the Ardennes countryside and forced to carry out agricultural work. According to the military authorities, this was a humanitarian measure intended to reduce the supply difficulties of the city. Five students were on the lists, including two from the Faculty of Law, Messrs Gardez and Jaeghère.

In 1916, Rector Georges Lyon, a philosopher by training, wrote a letter of protest to the German Chancellor denouncing this decision and pointing out that it contradicted the legal principles stemming from the Enlightenment philosophy. He invoked a common European culture supported by universities but did not succeed, as the military authorities considered that the measure was taken in the interests of displaced people :

“No one in this Germany, where the great educational communities which claim the name of universities drive wills at the same time as minds, will be surprised that the one named University of Lille loudly raises its voice to prevent, if there is still time, the execution of measures that would irreparably undermine the eternal principle that on either side of the Rhine all soul-shapers strive to make prevail […] They are free citizens who have not by any act, nor any violation of the rules of the occupier, deserved this sudden dispossession of their habeas corpus. […] But there is an aggravation of rigors that no theorist of war would want to justify, and it is here that stands the sovereign principle to which I referred at the beginning : this aggravation would consist in ignoring the inviolability of the human person. […] This principle, the greatest of your philosophers proclaimed it in immortal pages, as it had inspired the entire work of the greatest of our moralists. This principle, you and we inherited it from Rousseau and Kant ; we work tirelessly to engrave it in the hearts of successive generations on the benches of our schools and our universities. […] The day when it would fade away from human conscience would herald the mourning of every civilization […] Now I ask you, Excellence, with respect, without bias, without passion, such a principle, which is certainly at the front of your culture as well as of ours […] Let me invoke one last time the maxim of the one that our universities revere on an equal footing with yours, Immanuel Kant : the human person must be treated as an end, never as a means.”

On November 1st, 1916, notables were taken as hostages to Germany. The operation was intended to put pressure on the French authorities in the context of negotiations on Alsatian prisoners of war. A professor from the Faculty of Medicine was one of the hostages. A second hostage-taking took place in December 1917. Charles Mouchet, professor of Roman law, was taken to Lithuania.

During the year 1916-1917, Louis Vallas took advantage of the organization of voluntary evacuations to leave Lille and reunite with his family. To replace him, he recommended a lawyer named Massart, but he too was taken hostage. François Henri Dejamme then took charge of all civil law courses.

The fear of new waves of forced evacuations had a deep impact on the organization of university life. Students, mostly young men who could have been mobilized, represented a choice target, and the courses that brought them together were seen as opportunities for ambush. The timetables were hidden from the public and classes took place irregularly, without a recurring schedule. Without being completely clandestine, they were organized with discretion.

That same year 1916-1917, 51 students were enrolled at the Faculty of Law : the number of young not mobilized bachelors was increasing. However, only people residing in Lille, Roubaix or Tourcoing could take the courses : entry into the metropolis was prohibited. From October 1916 onwards, travel between Lille, Roubaix and Tourcoing was prohibited : students from these two cities could no longer attend classes. An extraordinary exam session was organized in December and January specifically for Messrs Gardez and Jaeghère, who had been released and authorized to return to Lille in November. Despite the limited time they had to prepare, they passed their exams (presumably with the help of the board’s benevolence).

A new wave of forced evacuations took place in June 1917. The rector managed to negotiate a postponement of a few weeks for the students on the list, arguing that they needed to take their exams. An early session was organized for them. The departure, which was simply to be postponed, did not take place in the end, and the students concerned were forgotten by the German authorities.

The same year, again to protect the students, the first day of class was moved ahead to October 1st (instead of November 1st) in order to occupy them as soon as possible and have an argument in case of requisitions for forced labor. This shift is also an opportunity to take advantage of longer and warmer days to teach in times of coal shortage for heating and lighting.

In 1917-1918, 73 students followed the courses of the faculty. In October 1917, the number of tenured professors present was reduced to three, and then to two when Charles Mouchet was taken as a hostage to Lithuania in January 1918. Paul Collinet provided all the Roman law courses. The professors were still assisted by volunteer lawyers, who took care of part of the courses. Mr. Viel, deputy inspector of registration, taught the political economy course, which had not been given since 1913-1914.

The end of occupation

On October 17, 1918, the German army left Lille. The human and material damage was considerable. Dean of the Faculty of Law Eustache Pilon, did not hide his bitterness in the annual report of the faculty : “the removed or broken tables, the no longer usable lighting and heating appliances attested there was no respect for the temples of science among the apostles of kultur”. These words reaffirm the tension within the academic world between the ideal of European fraternity based on a common scholarly culture, invoked by Rector Lyon in his address to the Chancellor, or experienced in the context of pre-war academic exchanges ; and the distancing of the enemy, the barbarians, favored by the anger resulting from the violence of battle. They also attested to the spread and impact of the patriotic discourse that makes the enemy the Kraut, the barbarian, the savage…

Even though resources were made available by the Ministry to restore the premises, the losses were also human. According to surveys carried out in the years following the conflict, 184 students enrolled in university in 1913-1914 died in the armed forces out of 1402, which is 13 % of the student body (a much higher percentage more if we count only those mobilized). A tribute ceremony was dedicated to them on January 17, 1921, highlighting the Franco-Belgian friendship. Paul-Emile Janson, lawyer and minister of war of Belgium, was made doctor honoris causa.

Regarding the Faculty of Law, the dean, anxious to assess the damage suffered by his community, started a survey of the families of students enrolled in 1913-1914. Despite a significant response rate (200 responses out of 351) given the circumstances, many families having moved or not returned home, Eustache Pilon estimated the percentage of students dead for France at 40 %, while the assessments mentioned above for the whole university estimated it rather at 13 %. A higher response rate among bereaved families could be an explanation. Two professors died in battle : Louis Boulard, about whom the dean underlined “the absolute dedication that he put, on all occasions, in the service of the students, going so far as to teach Latin to those who did not know it”, as well as Edgard Depitre.

Paying tribute to the deceased students in his annual report, the dean stated that their involvement in the war must be considered a commitment to the victory of the Law, referring to the legal dimension of the conflict the jurists committed to, and to its translation into war propaganda :

“They came to us to learn the law. And all of a sudden they became masters ; they gave the world the great lesson of law by offering their lives for its cause […]”

“While the followers of the theory of the “scrap-of-paper contract” militarily occupied part of the faculty, the voice of our teachers rose beside them to tell our students that under French law, the contract is the law of the contracting parties and that it must be executed in its letter and in its spirit.”

In addition to the two deceased professors, four were still serving in October 1918. At this point, four taught at the University of Paris : one had obtained his transfer in 1914, two were assigned to the Paris faculty after having worked there during the four years of war (they had not been able to return to occupied Lille) and Paul Collinet was transferred to Paris in 1918. The faculty was now reduced to five professors (the three remaining at the end of the occupation, two demobilized soldiers and two lecturers).

At the beginning of the 1918 school year, the number of students in the Faculty of Law rose to 105. Many youths were still mobilized, and inter-city movement, although allowed, was still disrupted, which did not facilitate attendance by non-residents of the metropolis. It took time for the faculty to return to its pre-war level of activity : only 249 students enrolled in 1919-1920, compared to 351 in 1913-1914.

In the field of research, two thesis defences took place during the year 1917-1918, which had not happened since the beginning of the war. On June 14, 1918, Félix Crémont defended a thesis titled “La Réforme du contentieux pénal des régies financières” [The Reform of the Criminal Litigation of Financial Authorities], while on October 21, Mr Mercier defended a thesis on occupational risk and agriculture (not present in the SUDOC document tracking system). Five theses were defended in 1918-1919, including a work by Henri Thellier titled “La succession du mobilisé décédé ab intestat” [The inheritace of the intestate war deceased]. The professors were able to resume their research work. In 1918, André Morel published a study entitled “Les marchés de fournitures des départements de la guerre et de la marine pendant les hostilities” [The supply contracts of the war and navy departments during the hostilities], while Albert Aftalion published on the French trade policy during the war (1919) and on the French textile industries during the war (1924).

Conclusion

The University of Lille continued to function during the occupation, independently and without the intervention of the German authorities in the organization of the study programs, a point which Alphonse Malaquin vehemently insists upon in his 1916 report :

“Our University has not undergone any control and at the time these lines are written. It must affirm that it will not tolerate any foreign interference either in the course of its moral and intellectual existence or in its independence as a great scientific institution.”

The occupation, the constraints and the destruction that it caused placed the University of Lille in a particular situation during the Great War. However, the remaining staff stood out in their commitment to keeping the institution in operation despite the difficulties : isolation from the rest of France, requisition or destruction of the premises, various shortages affecting the population, fear of bombing, forced evacuations and abductions, restrictions on freedom of movement…

The accounts of events contained in the reports written during and after the conflict show the persistence of a real academic community at the beginning of the 20th century, students included. Indeed, professors strove to allow students to continue their studies as much as possible and protect them from forced evacuations, going so far as to increase the number of exam sessions sometimes for only a handful of them. It is worth highlighting the role and outstanding personality of Rector Georges Lyon, who was also the university chairman.

The Great War and the suffering it caused also represented an earthquake among the academics, undermining the ideal of a common European culture inherited from the Enlightenment and the sharing of knowledge allowed by academic exchanges. It followed tensions already present before the war between the growth of international exchanges and the enrollment of scientific research in the competition between nations. The idea of peace became a fundamental concept in intellectual exchanges after 1919 as a means invoked to overcome these contradictions.

Geoffrey Haraux, Project Manager, Digital Libraries and CollEx Referent, Joint Documentation Service of the University of Lille

Bibliography

Annales de l’Université de Lille 1914-1919 : Rapports annuels du Conseil de l’Université. Compte rendu de MM. les Doyens des Facultés, Imprimerie-Librairie O. Marquant, Lille, France, 1925.

Annales de l’Université de Lille 1919-1920 : Rapports annuels du Conseil de l’Université.Compte rendu de MM. les Doyens des Facultés, Imprimerie-Librairie O. Marquant, Lille, France, 1921.

Aubry Martine, Matthias Meirlaen, Élise Julien, Helin Corinne, Condette Jean-François, Westeel Isabelle (dir.), Octobre 14. L’université commémore la Grande Guerre, 2014.

Condette Jean-François, « L’université de Lille dans la première guerre mondiale 1914-1918 », dans Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains, no 197, 2000, p. 83-102.

—, « Étudier et enseigner dans les facultés et les lycées lillois sous l’occupation allemande (1914-1918) », dans Revue du Nord, vol. 404‑405, no 1, 2014, p. 207‑239.

Condette Jean-François (dir.), La guerre des cartables, 1914-1918 : élèves, étudiants et enseignants dans la Grande Guerre en Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France, Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2018.

Lyon Georges, Souvenirs de guerre du recteur Georges Lyon (1914-1918), Villeneuve d’Ascq, France, Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2016.